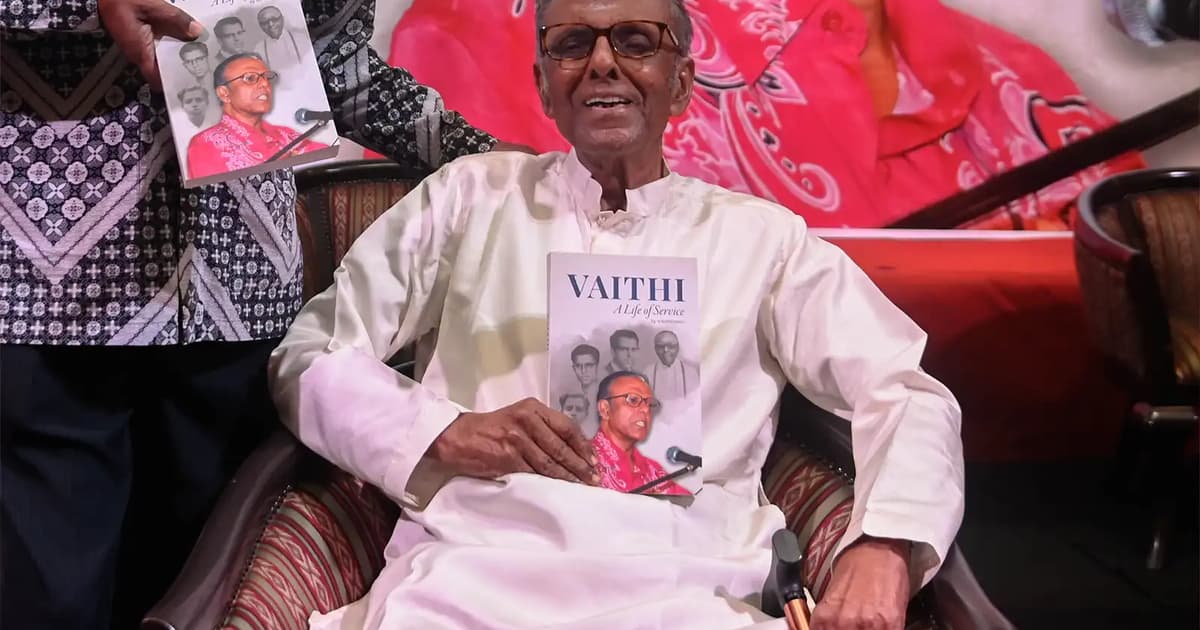

At 91, A Vaithilingam still talks about sport the way an athlete talks about a championship race – with urgency, clarity, and fire in his eyes.

Long before Malaysia had stadiums, scholarships, or sports science, he was among the men who built its foundations.

From muddy school fields to national councils, Vaithilingam helped shape athletics, football, and Olympic structures, driven not by titles or pay, but by a belief that sport could bind a young nation together.

“Sport is more than a game,” he says, voice steady despite the years. “It is where you learn discipline, respect, and how to live together. For Malaysia, it was the best way to unite people.”

His story, captured in the memoir “Vaithi, A Life of Service” by veteran journalist A Kathirasen, is a blueprint for how sport once carried the Merdeka spirit.

And in many ways, it is also a reminder of what has gone missing.

A sporting life before independence

Born in 1934, Vaithilingam grew up in a time when fields were rough and facilities scarce, but enthusiasm was endless.

He played football and athletics in school, not because medals were on offer, but because sport was a way to belong.

As a young teacher, he began organising games for students who had little more than chalk lines and borrowed balls.

What drove him was simple: “You cannot teach only with books. Sport teaches you character,” he says.

That belief carried him into sports administration. By the late 1950s, as Malaya approached independence, Vaithilingam was already making a name for himself in athletics circles.

He served in district and state sports councils, becoming part of the machinery that ensured sport was not just played, but structured, nurtured, and celebrated.

Sport as nation-building

The timing was crucial. A new nation needed symbols of pride, and sport provided them in abundance.

Merdeka Stadium was not only a place to watch football but a stage where Malaysians could see themselves as one people.

Vaithilingam, who later served with the Malaysian Athletics Federation, the Olympic Council of Malaysia, and the Asian Athletics Association, saw first-hand how athletes lifted national morale.

“When Malaysia won, everyone cheered together. No one asked who the player was, or where he came from,” he recalls. “That was unity.”

It was not glamour that kept him going. Sports administration in those days was voluntary, often thankless.

But Vaithilingam and his peers had stamina. They travelled by bus, slept in dorms, and spent their own money to keep teams running.

They believed the effort was worth it, “because sport was a patriotic duty.”

A man of many fields

Sport was the backbone of his life, but it also shaped how he served elsewhere.

The teamwork he learned on the field informed his leadership in education, religion, and community work.

He was active in teachers’ unions, part of a generation of educators who doubled as tireless coaches, nurturing talent across every sport and, in many cases, producing national stars.

He became president of the Malaysian Consultative Council of Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Sikhism, and Taoism, advocating for interfaith dialogue. He was also a voice in consumer rights movements.

Yet, in every sphere, his grounding was the same: the discipline of sport.

“In sport, you respect the rules, you respect your opponent, and you play fair. If we applied that everywhere, Malaysia would be stronger,” he says.

The endurance of passion

Looking back, Vaithilingam says it was passion that kept him moving through seven decades of service.

“Nobody paid us. We did it because we loved sport, and we wanted Malaysia to excel.”

That zest, he notes, is less visible today. Sports bodies often make headlines for disputes rather than development.

Facilities exist, but the fire is lacking. Too often, the focus is on medals and funding rather than on values.

Malaysia has more resources now than Vaithilingam’s generation could have imagined.

But what it lacks is the spirit – the endurance, selflessness, and joy of service that defined men like him.

His story is a reminder that nation-building requires sweat and sacrifice, not just budgets and slogans.

Lessons for Merdeka

As Malaysia celebrates another Merdeka, Vaithilingam’s life offers more than nostalgia. It is a challenge.

Where would the country be without people like him – volunteers who carried the Jalur Gemilang long before sponsorships or professional leagues?

Can we emulate his successes today? Perhaps not in the same way; his era was different.

But his values are timeless: enthusiasm without expectation, service without reward, harmony through shared struggle.

His book is aptly titled A Life of Service. But it is also a life of stamina.

He treated service the way athletes treat training: daily, disciplined, often unseen. That is what gave Malaysia its early sporting lift.

A patriot’s independence

When asked what Merdeka means to him, Vaithilingam does not speak of politics or parades. Instead, he recalls athletes walking onto the field with Malaysia’s flag for the first time.

“That was freedom. To see our flag, to know we were competing as Malaysians – that meant everything.”

His memory remains sharp, his stories rich with detail. But more than memory, it is his conviction that endures: sport gave Malaysia dignity, and Malaysians must not forget it.

“Keep the fire alive,” he urges. “Don’t let sport become only about winning. Let it be about building people, and building Malaysia.”

A rare Malaysian

Profiles like Vaithilingam’s are rare today. He belongs to a generation that saw service as duty and sacrifice as natural.

His kind kept the Jalur Gemilang flying when the country was still learning to stand.

Perhaps the best tribute is not to celebrate him as a relic of the past, but to recognise him as a coach for the future.

His playbook is clear: passion, endurance, and togetherness. The question is whether today’s Malaysia has the stamina to follow it.

To purchase ‘Vaithi – A Life of Service’ contact 03-2698 9199.