Her family home was always abuzz with activity, unlike any other. Whether she was having breakfast or finishing homework with her cousins (who grew up in the same house), Deva Kunjari was a witness to a stream of people who dropped by to see her father, seeking his help and counsel.

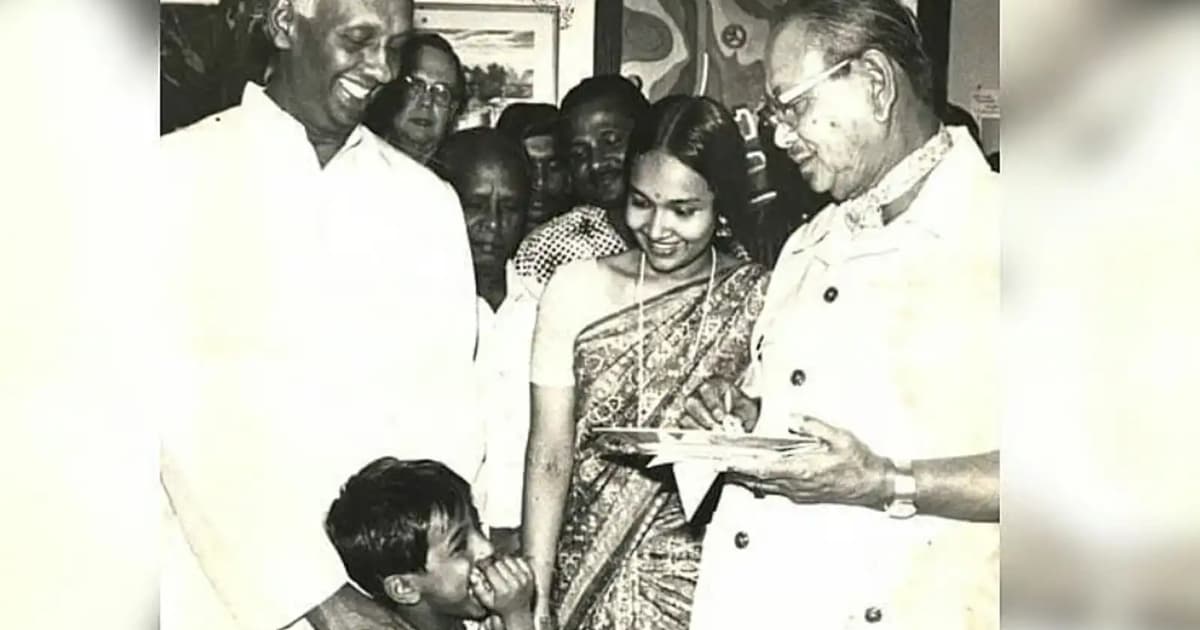

Yet despite being MIC president and a cabinet minister in a fledgling government, her father, the late VT Sambanthan, always made time for her.

“No matter how busy he was, he was there for us. We were used to him being around people, but somehow always being available to us. It could just be a few minutes at the meal table,” Kunjari, a lawyer, shared with FMT Lifestyle.

For her, this balance between public duty and familial love defined their bond. She described her relationship with her father – one of the signatories of the 1957 Merdeka Agreement and Malaya’s first labour minister – as “extremely close”.

She said he even found time to tell her bedtime stories of his own creation. “And through his bedtime stories, he taught me about agriculture and politics.”

Sambanthan, the first MP for Sungai Siput, held several ministerial posts but to Kunjari titles never changed him.

“Whether he was a politician, a father, an uncle, a brother, he was always the same person,” she said. “He never treated people as being less than he was or we were.”

It was only later that Kunjari began to grasp the weight of his position. She admitted she had no inkling of his importance to the country as a child. Sambanthan was a minister until August 1973, when he briefly became acting prime minister while Abdul Razak Hussein and his deputy Hussein Onn were abroad.

“He was very down to earth about whatever position he carried. I think it was always for him a question of what he brought to the table and how much he could serve,” Kunjari pointed out.

This sense of service was shaped by his roots. The son of Indian migrants, Sambanthan witnessed life in the estates where his father, Andiappan Veerasamy, who arrived in Malaya in 1896, was a rubber planter.

From that life, Sambanthan saw the struggles of estate workers, and the need to give them dignity and a voice.

In 1960, he founded the National Land Finance Cooperative Society to protect Indian workers as plantations fragmented. Kunjari still recalls him sketching its logo at the dining table while she and her cousin did schoolwork.

“He sat next to us. He drew a tree and then he wrote the words c-o-o-p in the form of a tree and that’s the logo. He turned to us and asked, ‘What does it look like?’. We said ‘nice’. So, that was how he did things. He didn’t treat us as kids,” Kunjari said.

Her father’s belief in fairness reached beyond his community. While he championed Indian workers, home life reflected a wider Malaysia. Her mother arranged Jawi and Mandarin lessons, and the children were introduced early to the mak yong, menora, and East Malaysian culture.

“We embraced everything. We were not brought up to regard something as being ours and not anything else,” said Kunjari, adding that Sambanthan played a crucial role in lifting the ban on the Chinese lion dance in the early 1970s.

“We were raised to respect and assimilate as part of our heritage that which is a component of being Malaysian.”

More than his cultural worldview, it was Sambanthan’s values that shaped Kunjari’s life.

“He was kind to everyone, regardless of race. He saw no distinctions. I try not to see distinctions between people. He was honest. I try to be honest.”

But, she quickly added that “I don’t think it’s possible to emulate what he did because he was a natural.”

Looking back on her father’s legacy and her own hopes for the nation, Kunjari returns to the lessons of that lively home – where unity was nurtured amid diversity.

“He used to say: many races, but one people,” Kunjari recalled. “He was very proud of the fact that although we were so many strands, we came together organically, naturally, and coherently.”

This Malaysia Day, she said it was her hope that Malaysians can recover that same spirit: “We need to grow as a people, and not be divided”.