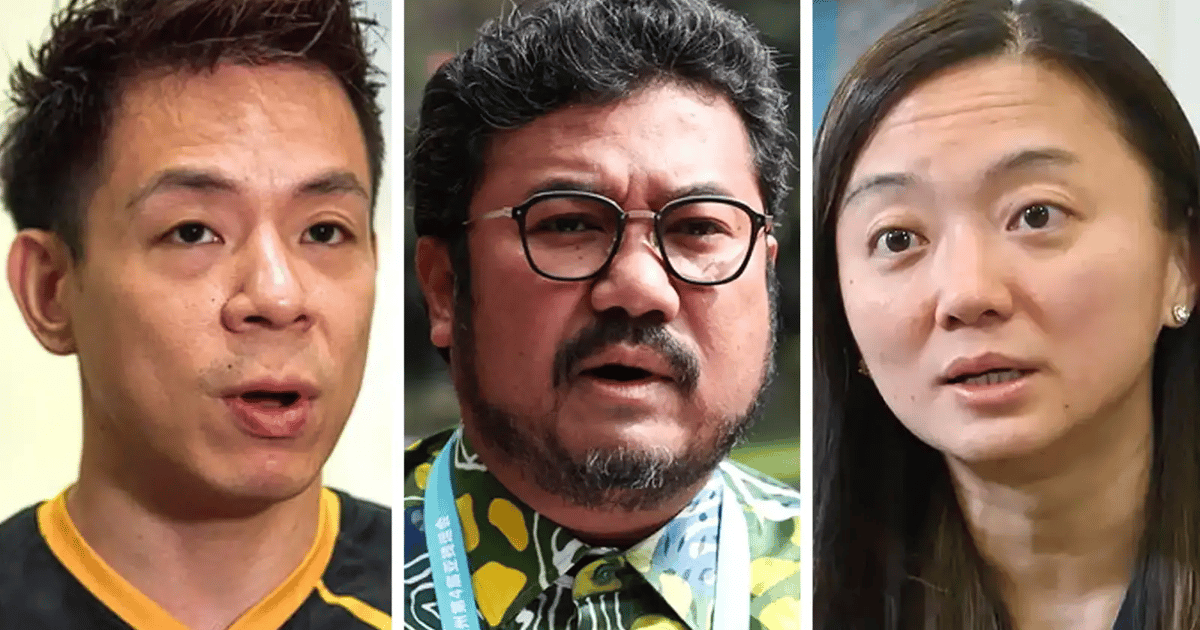

Para badminton player Cheah Liek Hou’s Instagram post was brief, but it rattled Malaysian sport.

“It feels like they scammed me,” he wrote, still waiting for the Paris Paralympic gold medal reward more than a year later.

For Cheah, it was raw frustration. For the Paralympic Council of Malaysia (MPM), it was defamation – a slur on the council’s reputation and grounds for legal action.

Technically, MPM has a case. “Scam” implies fraud, and organisations, like individuals, can defend their reputations in court.

But in the public eye, the word was heard less as a criminal charge and more as an athlete at breaking point.

That is why MPM’s next move is crucial. No institution wins by suing its own champion.

Protecting its name on paper may cost it far more in public trust. Institutions gain little by silencing the very athletes they exist to support.

MPM president Megat D Shahriman Zaharudin took the harder line.

He warned that Cheah’s outburst could even cost him a place in future multi-sport events like the Olympics and Asian Games – a threat youth and sports minister Hannah Yeoh quickly shot down, saying they can’t simply do that.

Megat also argued that athletes must be careful with their words:

“When an athlete publicly accuses an organisation or sponsor of unethical practices, it can have a ripple effect. Sponsors may begin to reconsider their partnerships, and public perception can shift quickly.

“It’s essential to remember that every word shared on public platforms carries weight, and athletes, as public figures, must be cautious about the image they project.”

Yet here lies the irony. It wasn’t Cheah’s Instagram post that eroded confidence, but the reward delay itself.

Sponsors, like the public, look for reliability. Broken promises damage trust far more than a frustrated word on social media ever could.

Yeoh sensed this. By calling Cheah’s case one of delays, not discipline, she reframed the conflict.

Her defence was careful: she avoided endorsing the word “scam” but upheld his right to demand what was promised.

The message to sports bodies was clear – listen first, punish later, if at all.

Yet this too has a flipside. It may embolden athletes to go public more bluntly, and if such leniency is not extended to critics of the ministry itself, questions of consistency will arise.

What makes Cheah’s post so stinging is not just the word, but the history behind it.

Athletes in Malaysia have long been told rewards are coming – sometimes weeks late, sometimes years.

Excuses vary: budgets, procedures, “waiting for sponsors”. Over time, the pattern breeds cynicism. Each delay chips away at trust.

Malaysia already has one solution: the national sports incentive scheme (Shakam). Its fixed sums and clear timelines leave no room for ambiguity.

MPM’s reliance on goodwill may have been well-meant, but goodwill is no defence against anger when promises drag.

This is why optics matter as much as legality. Taking an athlete to court may feel like control, but it looks like weakness.

The other path – reform – builds strength by preventing such flare-ups from recurring.

Cheah’s words may fade from headlines. What will endure is how institutions choose to respond – with pride, or with structures strong enough that no athlete feels compelled to use that word, scam, again.

The views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of FMT.