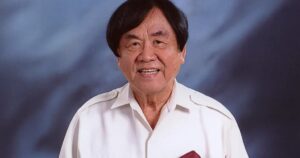

A strong sense of political identity is the bedrock of any functioning federation, says London School of Economics president and vice-chancellor Larry Kramer.

Nations cannot survive without a shared political identity that binds citizens together, despite their differences, Kramer said in an FMT interview.

“Before you even think about whether (a country) is going to be federated or not, you need a sense of shared political identity. If the differences get too deep so that people no longer see themselves as part of one political community, then it’s not going to work no matter what structure you use,” he said.

Kramer described this political identity as a kind of common denominator, whether tied to security, culture or religion, that allows citizens to see themselves as part of the same whole. He said this sense of belonging must be reinforced through education, so that every generation understands it and carries it forward.

Without a unifying political identity, federal structures risk collapsing under the strain of conflict, he said. “A lot of the problems in the world today actually come more from a loss of shared political identity than anything else.”

He added that when citizens see themselves as part of a common national project, they are more willing to accept compromises and live with outcomes they might not personally favour.

Kramer, who was previously the dean of Stanford Law School, said federal systems thrive when decision-making powers are properly balanced between national and state levels.

“Some decisions are best made at a large national level because they affect everybody. Others are better made locally because they’re going to affect people differently.

“Being close to the ground always makes sense, because the closer people are to the decisions that affect them, the more likely they are to accept them, even if they don’t necessarily agree,” he said.

International models of federalism

Kramer said the American system tried to address this balance by making federal law supreme while giving states a direct role in national politics.

“In the US, the national government was given a lot of power, and its decisions would be supreme whenever they conflicted with state law.

“But the system also ensured that states were directly represented in the national government, with elected representatives carrying their state interests into Congress,” he said.

In the US, Congress is split into two chambers: the House of Representatives, where seats are based on population, and the Senate, where each state has two senators regardless of size.

This was designed to balance the influence of large and small states, ensuring that national laws reflect both the will of the people and the interests of the states.

He also cited the European Union’s principle of subsidiarity — making decisions at the most local level possible — as a model that can help nations to balance unity with diversity.

The principle, embedded in the EU’s treaties, ensures that decisions on issues like education, healthcare or local infrastructure remain close to the people affected by them, while broader matters such as trade, environmental regulation and cross-border security are coordinated at the continental level.

However, he said that while courts can serve as arbiters in disputes between state and federal authorities, judicial supremacy is not always healthy for democracy. Even judicial power must remain accountable to society’s broader direction.

“Using the judiciary is one way to umpire disputes, but if you do it in a way where its decisions are final no matter what, it amounts to saying the people have decision-making power except for the really important things, which we’ll hand over to a small oligarchy,” he said.