THERE was a time when entering into a contract was as simple as ABC. The company handed you a contract and you sign off if the terms were acceptable. When you wanted to end the service, you pay the current bill and that was it.

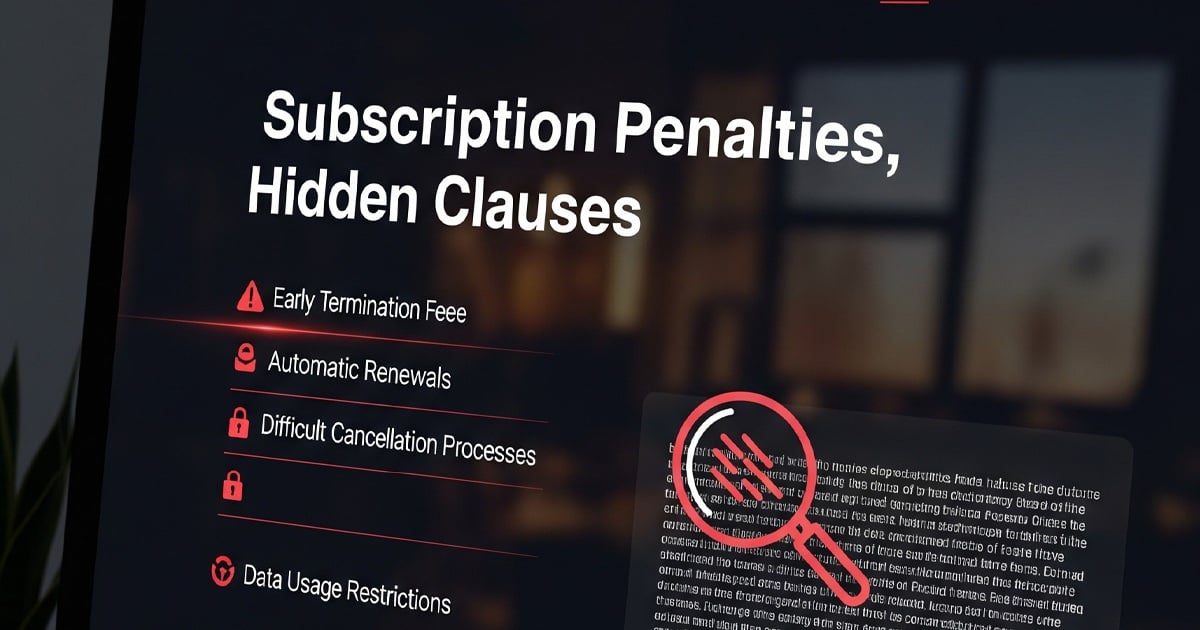

But with competition getting intense, businesses have become creative by inventing the subscription contract that comes with a self-renewal clause, unless terminated with notice. And the auto-renewal clause comes with a termination penalty. As high as RM58,000 for quitting a wellness programme, as one complainant told the National Consumer Complaints Centre (NCCC).

Herein lies a trap. When you try to unsubscribe from the service, it is like searching for a needle in a haystack. If you managed to do so, you end up paying a hefty penalty.

Is this legal? Here, we come face to face with the “on the one hand and on the other hand” argument of lawyers. As a general legal principle, a contract is an agreement between parties. Were the terms made explicit to the consumer? If so, then the consumer’s case ends there, except if the penalty is excessive, like the RM58,000 imposed by the wellness company.

In such cases, it is best to proceed to the Tribunal for Consumer Claims. Vigilance is the key. But being vigilant isn’t easy in a business environment where companies push the concept of consent to the edge of the law.

Complaints to the NCCC tell us that the subscription contracts need regulatory intervention. Not that Malaysia doesn’t have laws. It has several, but unlike the United Kingdom, not specific to subscription contracts.

Do we need one? Certainly, but first, let’s look at what we already have. The Contracts Act 1950 (CA) is one of several. Subscription agreements are contracts, they clearly fall under it. The CA makes consent of the parties a critical element.

Another, and perhaps more relevant, is the Consumer Protection Act (1999), which specifically addresses unfair contract terms. Astronomical penalties, either made known or hidden, are likely to be treated as such. So will deceptive auto-renewals.

Finally, the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 (CMA). Interestingly, the CMA imposes a duty to act reasonably on all service providers. If the auto-renewals and penalties are not made known to and agreed by the consumer, then the service providers could be found to have failed in their duty to act reasonably.

A point needs to be made, though. Despite scores of complaints to the NCCC, there has been no litigation on such issues. Neither have the regulators acted on the complaints, Perhaps, they are waiting for the consumers to lodge a report with them.

A report from the consumer shouldn’t be the only way for regulators and enforcement agencies to act. Even the police are using viral videos to launch their investigations. The regulators must go where the complaints are: consumer associations, NCCC and media reports.

Malaysia needs a specific law such as the UK’s Consumer Contracts (Information, Cancellation and Additional Charges) Regulations 2013. Proper consent of the consumer, together with a cooling-off period of 14 days, is a pillar of these regulations.

The UK doesn’t just have specific laws, but dedicated agencies to enforce them. Copy that, Malaysia?

© New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd