PUTRAJAYA has set an ambitious target of being among the top 25 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index by 2033. But it appears that the eight years remaining may not be enough to meet its target.

Here is why. Firstly, it has to add two points every year. In 2023, it scored 50 points out of 100.

Last year, it maintained the score at 50 points, keeping it trapped at 57th position. To get to be among the 25, Malaysia needs to score at least 69 points.

To score 19 points in eight years isn’t going to be easy, especially when business and country experts, whose assessment plays a vital role in the ranking, want to see Malaysia implement more reforms.

To provide context, Denmark — for the seventh consecutive year — was ranked No. 1 with a score of 90, while Finland second with a score of 88 and Singapore third with a score of 84. Our other Southeast Asian neighbours are all ranked lower.

We may take pride in this, but comparing countries that are ranked lower isn’t going to make our ambition of being among the top 25 come true. Looking at which countries are ranked higher and why will.

Secondly, every other day we read reports of public sector officers, even very high ranking ones, being arrested for corruption. This is no way to get the country to the top 25, let alone rush it there.

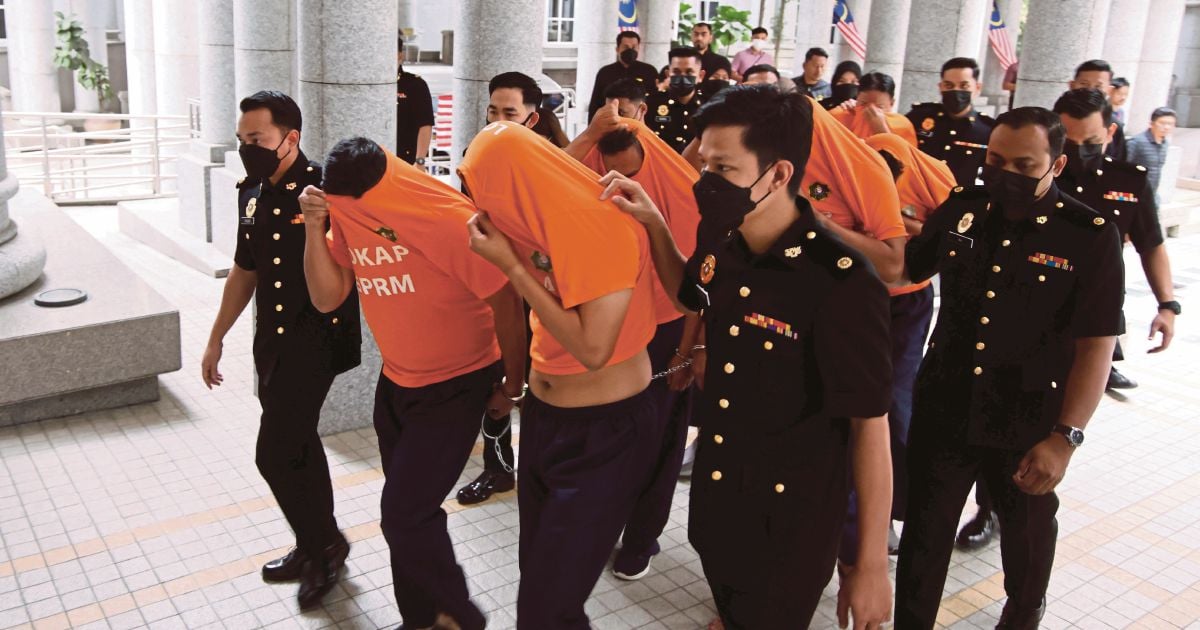

Yes, eight years is not enough. The latest case that shocked the nation was the arrest earlier this month of five serving and former military officers by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission.

They were said to have direct links to a tobacco, cigarette and cigar smuggling ring busted on Tuesday.

This raises a bigger concern: just how deep is the protection network between smugglers and enforcement officers? Very deep, deeper than initially thought.

The graft busters are closing in on enforcement officers from several agencies acting as “facilitators” for the smugglers.

Initial investigations by MACC appear to point to the smuggling being orchestrated by a handful of officers who provided easy access for the goods to be smuggled in through various entry points. It doesn’t stop there.

The miscreant officers protect the syndicates’ warehouse operations when they should be taking enforcement action.

When enforcement officers become smugglers’ partners-in-crime, then we know there is an eruption of corruption in Malaysia. There is no point in brushing them aside by tagging them as isolated incidents.

Enforcement agencies, including the armed forces, will do well to dig deeper to see if there are more miscreants in their midst than meet the eye.

Police have done a good job by owning up to the presence of corrupt officers, even among the senior ranks. Others must do the same. Trust will follow transparency. The beginning of a solution to any problem is to recognise its existence.

Corruption is certainly a problem, and a national one at that. Our media reports so often show it to be so.

The curious will ask: how did Denmark manage to be ranked No. 1 for seven years? Not rocket science. The Nordic country holds the corrupt to account. Malaysia must do the same.

© New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd