FROM translating thoughts into words to allowing paralysed people to walk, the field of neurotechnology has been quietly surging ahead, raising hopes of medical breakthroughs — and profound ethical concerns.

Some observers even think that neurotech could end up being as revolutionary as the far more hyped rise of artificial intelligence (AI).

“People do not realise how much we’re already living in science fiction,” said King’s College London researcher Anne Vanhoestenberghe.

The scientist leads a laboratory developing electronic devices which are implanted into a person’s nervous system — not just the brain, but also the spinal cord that transmits signals to the rest of the body.

It has been a big couple of years for neurotech research. In June, Californian scientists revealed that a brain implant they developed could translate the thoughts of a man with the neurodegenerative disease ALS into words almost instantly, in just one-fortieth of a second.

Swiss researchers, meanwhile, have enabled several paralysed people to regain significant control of their body — including walking again — by implanting electrodes into their spinal cords.

These experiments, and other trailblazers in the field, are still far from restoring full capability to patients who have lost the ability to talk or walk.

It also remains to be seen how such technology, some of which requires invasive brain surgery, could be made available to people in need across the world.

But still, “the general public is unaware of what is already out there and changing lives”, said Vanhoestenberghe.

And these devices were becoming more effective at a remarkable rate, she emphasised.

“Previously it took thousands of hours of training before someone could compose several words using their thoughts,” she said. “Now it only takes a couple.”

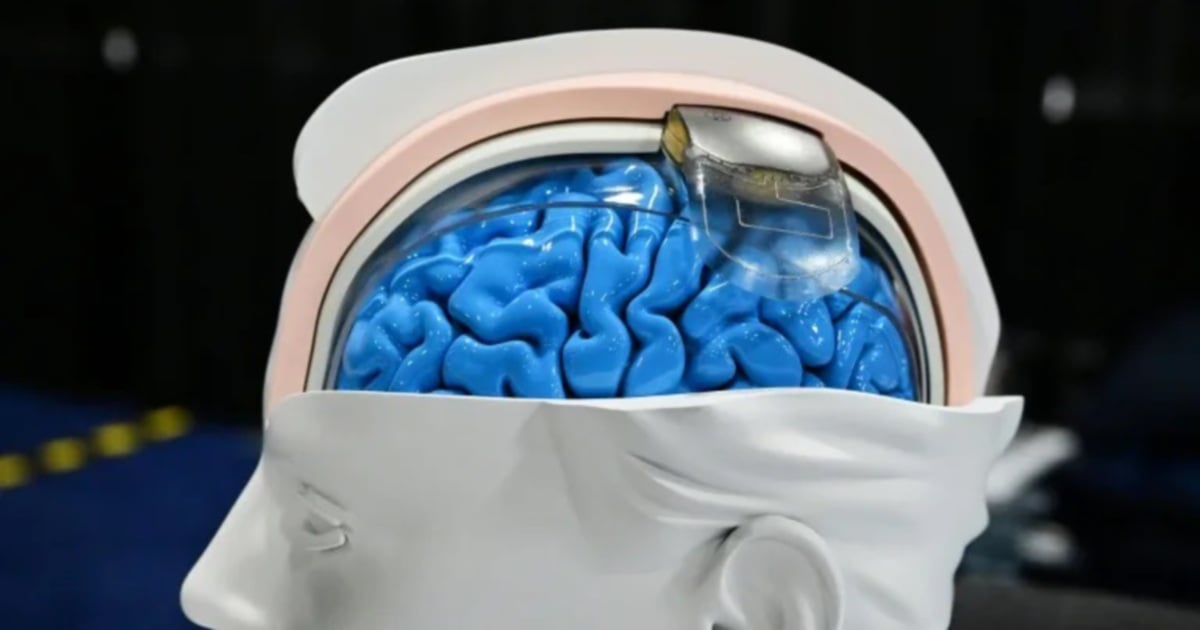

Neurotechnology has been propelled by a combination of scientific advances — including growing understanding of the human brain — and technological progress which has shrunk devices down so small they can slot into our skulls.

Algorithms using AI have sped things along, helping to interpret and transform the data coming from brains.

Numerous startups that have emerged since the late 2000s have raised tens of billions of dollars for research that has only recently started translating into concrete achievements.

The most publicised company is Elon Musk’s Neuralink, which says it has now implanted 12 people with its chip.

While Musk has made characteristically lofty claims, experts have remained cautious about his firm’s accomplishments.

“Neuralink is currently just smoke and mirrors, with a lot of hype,” said Herve Chneiweiss, a neurologist and expert in ethics at France’s research organisation INSERM.

However, “the day they manage to produce commercial products — and it won’t be long — it will be too late to worry about it,” he cautioned.

Many experts are concerned about the ethical implications of neurotechnology — particularly because some companies are looking well beyond healthcare applications, instead hoping to use computers to improve our cognitive abilities.

Musk, for one, has repeatedly said he ultimately wants Neuralink to allow humans to achieve “symbiosis” with AI.

Against this background, the United Nations’ agency for science and culture Unesco recently approved recommendations for how nations can regulate neurotechnology.

The authors, who include Chneiweiss, adopted a broad

definition of neurotech. It includes devices already widely available such as smartwatches and headsets that do not directly interact with the brain, but instead measure indicators providing an idea of the user’s mental state.

“Today, the main risk is invasion of privacy: our innermost thoughts are under threat,” said Chneiweiss.

He warned, for example, that neurotech data could “fall into the hands of your boss”, who could then decide that you are not spending enough time thinking about work.

Some have already started trying to address such concerns.

Late last year, California, a global hub of neurotech research, passed a law protecting the brain data of consumers.

The article is from AFP

© New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd