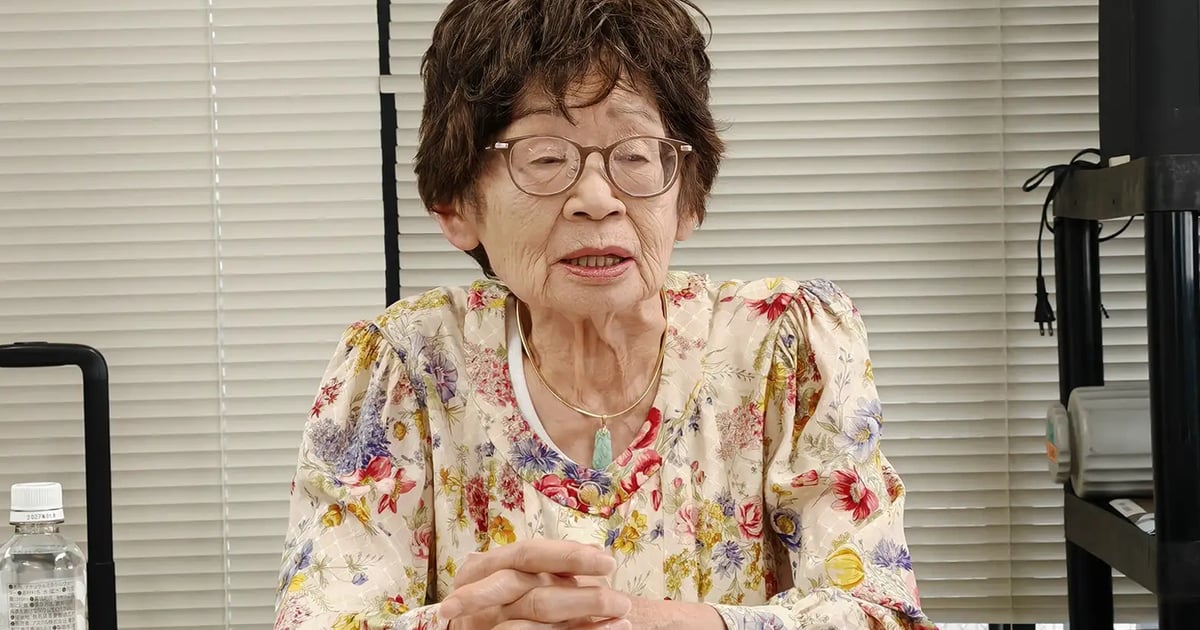

Katsuko Kuwamoto was born in 1939, into a country already at war with the world.

By the time she entered elementary school in April 1945, her father had already been sent to the battlefield, swallowed by a war that devoured men as quickly as it starved women and children.

Families were left with only mothers, children, grandparents and little else. “We didn’t have food. I was always hungry,” she recalled.

One month into her first school year, the children were ordered to evacuate from central Hiroshima. Firebombing had already reduced other cities, including Tokyo, to cinders.

Katsuko and her older sister were sent to their aunt’s farm on the edge of the city.

“There were already four other families packed into the house. One family lived in the barn. Another in the tool shed. Everyone was hungry. Everyone was angry.

“When food went missing, the blame always came to us. We had no parents with us. No one to defend us.”

Still, every Saturday, Katsuko and her sister made the long walk home to see their mother in the city. They would stay one night and return to their aunt’s on Sunday evening.

“We cried. We begged her to let us stay. We said: ‘Even if a bomb drops on us and we die, we want to die here with you.’”

But fate, disguised as well-meaning neighbours, intervened.

“Our neighbours told us: ‘If a bomb falls, your mother won’t be able to escape with two children.’ So we went back to the farm. That was the afternoon of Aug 5, 1945.”

The next morning, Katsuko got up like it was any other school day. She made her way to class, unaware that a US bomber had already crossed the sky.

By then, the city had grown used to the sound of American bombers. When the air raid sirens blared, people took cover. But that day, there were no sirens or warnings. Just the low thrum of a B-29 heavy bomber.

That morning, with the adult male population sent to the front, children were mobilised to labour outside, tasked with demolition work, dismantling homes and making firebreaks.

As the school bell rang, Katsuko stepped into her classroom. One of her classmates was playing by the window.

Above their heads, something shimmered. A metallic glint against the morning sky, tumbling and spinning while the children outside stared.

At 8.15am, the atomic bomb detonated. Ten seconds later, a deafening boom split the city apart. The shockwave shattered the windows of the school, 3.5km from the hypocentre.

“My classmate who was playing by the window was shredded by shards of glass. Her blood sprayed like a fountain.

“The teacher picked her up in his arms and ran around the schoolyard in a panic. His face was pale, distorted with suffering.”

The children didn’t understand what had happened. They clung onto their teacher’s clothes and followed. Katsuko’s aunt arrived soon after and took them home.

The students working outside that morning weren’t as lucky. They were incinerated instantly. All that remained were their shadows, scorched into the ground as memorials to lives cut short.

The search for mother

That same morning, Katsuko’s mother stayed home, 1.3km from ground zero, feeling slightly unwell. She was eating a late breakfast when the bomb fell.

In an instant, the blast crushed the house around her. Trapped under splintered beams, she screamed until a neighbour clawed through the debris to rescue her.

Worried about their mother, Katsuko’s cousin offered to go look for her, armed only with a rucksack and a water bottle. But he was back in under ten minutes. The firestorms and the terrain made it impossible to reach the city.

Three days passed before the flames quieted. Katsuko, her sister, and their aunt finally entered the city. When the smoke finally lifted, what lay beneath was nothing short of a hell made of bone and ash.

“We saw dead bodies everywhere. We couldn’t even make out where the houses and fields had been. We found nothing but charred corpses,” Katsuko said.

“Even the ones who were still alive, you couldn’t tell if they were men or women. Their faces were swollen one and a half times the normal size. Their clothes had burned off.”

After hours of searching, they turned back defeated. Nearly a week after the bomb fell, Katsuko’s mother came to them on foot, through the radioactive rain and ruins.

“She looked okay at first, but her face was pale. So pale it was blue. I’ve never seen such colour on a person’s face before. She tried to talk but just vomited blood.”

Residents of Hiroshima called the bomb “Pikadon” — “pika” for the flash, “don” for the boom. No one yet understood the bomb’s true radioactive nature.

“She was dying. But then our father came home from the war, and they had the same blood type. There was a rumour that blood transfusion might help. So he gave his blood to her, every day.”

Months later, in early winter, Katsuko and her sister were playing outside when they saw a figure on a bicycle. It was their father. On the back, their mother was alive, smiling.

“They told us every day that she would die the next day, but she lived. The rumour that blood transfusion helped was true.”

But in the years that followed, her mother’s body began to fail. She developed breast cancer, then lung cancer, and eventually tumours in her brain, to which she later succumbed.

The long war

The war officially ended on Aug 15, 1945, but the aftermath lasted decades. Food shortages continued, forcing families to sell their prized kimonos for rice. School resumed outdoors as there were no buildings. When it rained, classes were cancelled.

Around 80,000 people were incinerated in an instant by the bomb. Estimates say nearly 200,000 had died later from its lingering effects.

Even after witnessing the destruction of her city and the loss of friends, neighbours, and family, Katsuko, like so many survivors, chose not to hold hatred toward the Americans.

“None of my family members were seriously injured by the bomb itself, but we never received any compensation from the US.

“I didn’t feel any resentment. Later on, I went to a missionary school. My teachers were American. They were kind people and good teachers. There’s no use in hating them.”

At 86, Katsuko believes the key to a long life isn’t holding on to anger, but rising early, walking her dog and continuing to speak. What drives her is the hope that through awareness and testimony, others might finally understand the human toll of war.

“We’ve had more visitors from the US lately. It seems the belief that the bomb was a necessary evil is fading, even in the US.

“We should never have war again. There’s nothing more stupid than war.”