Experts say regulatory ambiguities around engagement-boosting services have enabled scams, online manipulation and digital fraud

PETALING JAYA: The booming trade in paid “click farming” services to artificially inflate likes, views and comments on social media is operating in a legal grey zone in Malaysia, with experts highlighting that the same engagement-boosting infrastructure is increasingly being repurposed for scams, fraud and online manipulation.

Malaysia Cyber Consumer Association president Sirajuddin Jalil said click-farming operations rely on large-scale automation using so-called “phone farms”, enabling a single operator to control hundreds or even thousands of mobile devices at the same time.

“At the moment, regulations do not directly address click farming. There is no law that limits how many mobile phones a person can own. However, there are laws that limit SIM card ownership.

“For example, if someone has five prepaid SIM cards, that is already illegal because they would have to register them under other people’s names or use fake identities.

“To run a click farm, you need a phone farm connected to software on a computer. One computer can control hundreds or even thousands of phones. Each phone can have multiple social media accounts.”

He said such systems allow operators to generate vast volumes of engagement with minimal effort.

“With one click, someone can generate 1,000 likes on a post. They can also instruct bots to leave comments using AI-generated text. It looks real and triggers the platform’s algorithm.”

Sirajuddin warned that artificial engagement creates a false impression of popularity or credibility, shaping how users perceive online content.

“When people bypass official advertising platforms and instead pay click-farm services, it becomes a risk not just to users, but to the platforms themselves. More importantly, this infrastructure is often reused for scams.”

Universiti Malaya cybersecurity specialist Prof Dr Ainuddin Wahid Abdul Wahab said the normalisation of click farm services had enabled large-scale fraud and expanded cybercrime infrastructure globally.

“Bot fraud now accounts for about 65% of connected TV (CTV) fraud globally, potentially wasting around US$700,000 (RM2.8 million) for every one billion impressions,” he said, citing DoubleVerify’s 2025 Global Insights report.

From a cybersecurity standpoint, he said click farms rely heavily on automation, bot orchestration and compromised or fabricated accounts, significantly increasing exposure to phishing and identity theft.

“Click farms do not create content or narratives. They amplify whoever pays. Scammers use them to ‘warm up’ fraudulent pages with fake testimonials so that victims see what looks like social proof.

“Once fake engagement becomes normalised, it becomes a tool for ‘astroturfing’ (the deceptive practice of presenting an orchestrated marketing or public relations campaign) which manufactures popularity to influence consumer behaviour and public opinion.”

Despite the risks, industry practitioners say artificially boosted engagement has become a routine part of campaign strategy.

An industry source familiar with multinational campaign management said spending on digital engagement is commonly built into campaign planning and treated as a legitimate visibility tool.

“In most campaigns, engagement is discussed early on, alongside content and media planning. It’s not something that comes later. It’s already part of the strategy.

“(High) traction has become a form of credibility. The huge numbers of likes, views or comments are often used to show that a campaign is performing well.”

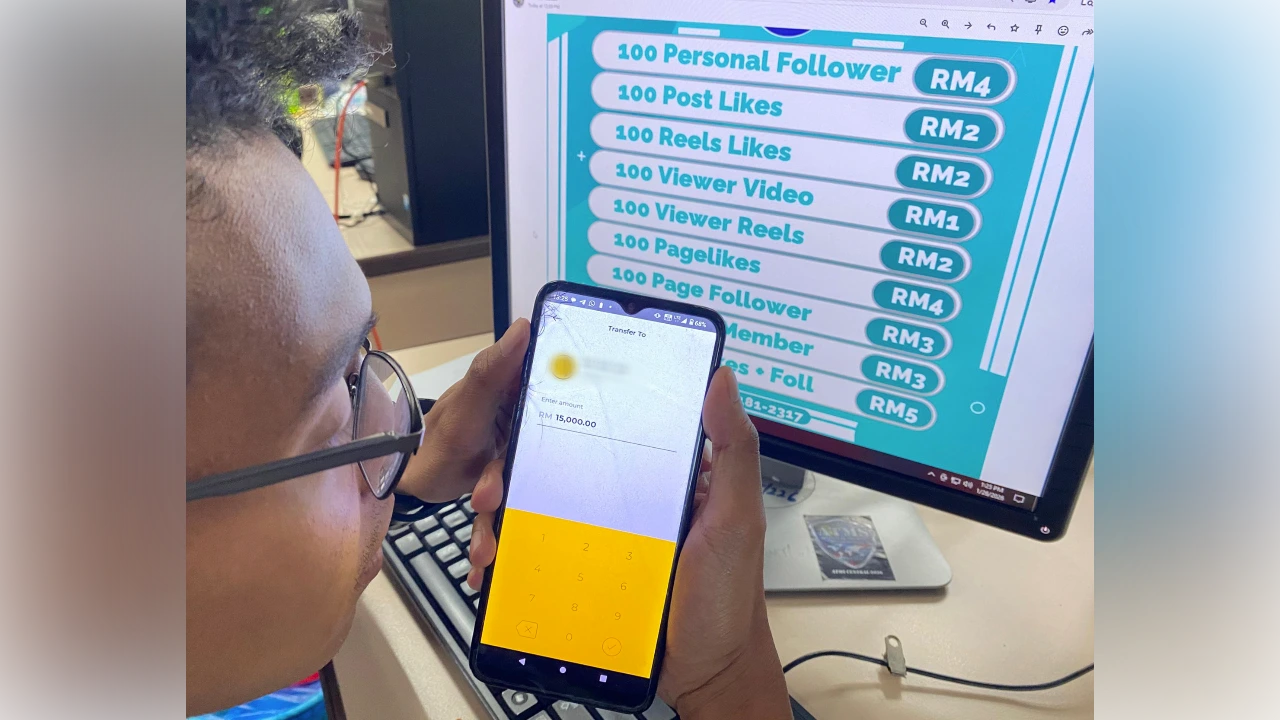

He said budgets for engagement-related spending vary by campaign, with some allocating several thousand ringgit and others reaching up to RM15,000.

“Engagement usually comes through third-party vendors offering likes, views or comments as part of a broader campaign package, sometimes layered on top of platform ads.

“It’s usually tied to visibility goals such as boosting reach, making posts look active early on or helping content gain momentum. Clients don’t usually ask which vendor is used or how engagement is generated. What they want to see is movement – likes, views, comments – that shows traction.”

He added that there is little industry concern over enforcement, as click-farm-style engagement is widely viewed as operating within platform rules or regulatory grey areas.