In the corridors of constitutional law, it is common to witness the importation of foreign doctrines into our legal framework — often without rigorous scrutiny of their compatibility with our constitutional ethos.

This practice, sometimes theatrically advanced by advocates, has led to a jurisprudential landscape shaped more by borrowed wisdom than indigenous insight.

Rare indeed is the occasion when a doctrine, born within our own judicial womb, finds its way into foreign jurisdictions — exported not by accident, but by design.

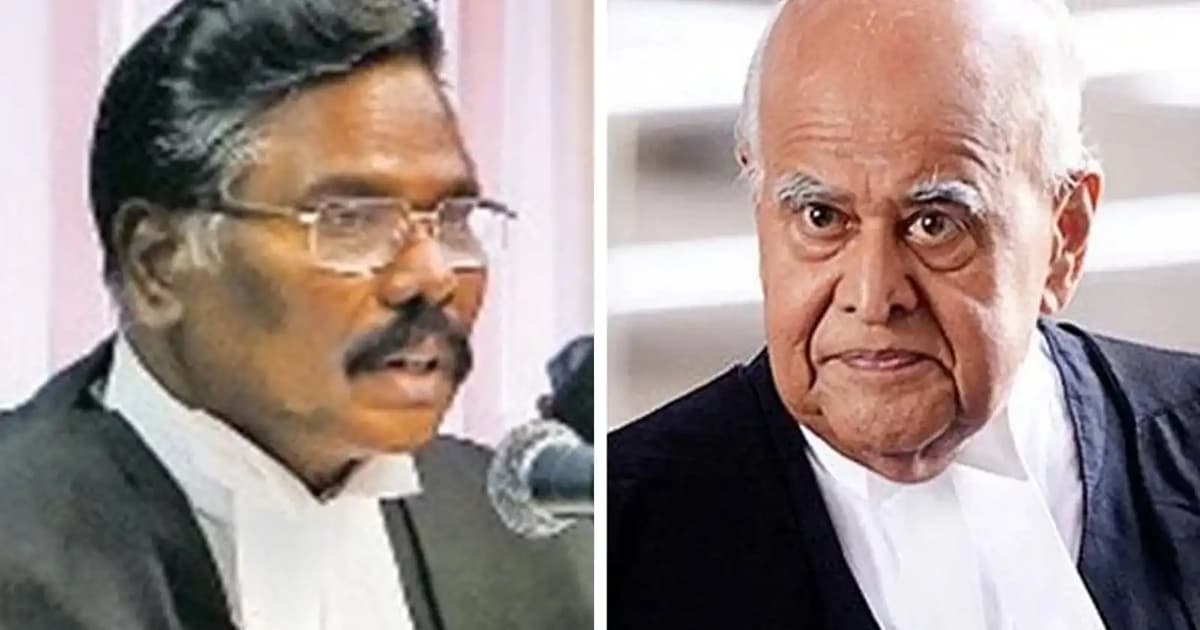

The late Justice V. Dhanapalan, of Tamil Nadu in India, was one such jurist who not only understood this possibility but actively encouraged it.

I had the privilege of engaging with him during my tenure as a Court of Appeal judge. At a legal function, I introduced to him my jurisprudence on the oath of office — a doctrine I had developed through a series of judgments, rooted in the rule of law and designed to test arbitrariness in governance.

This doctrine integrates established principles such as reasonableness, proportionality and accountability, and applies them not only to the legislature and executive but also to the judiciary.

The essence is simple yet profound: once the three pillars of government take their constitutional oath, they cannot remain passive seat-warmers. They are bound by that oath to act. Any failure to do so must be subject to judicial scrutiny. The phrase “work-in-progress” cannot be a shield against constitutional accountability.

Dhanapalan was visibly stunned. “Why has this not been adopted by the Indian judiciary,” he asked, noting that the oath is identical in spirit across Commonwealth jurisdictions.

At the time, he was preparing to launch his book, Basic Structure of the Indian Constitution — Overview, and expressed regret that it was too late to incorporate my work. Yet, he acknowledged its uniqueness, pointing out that unlike Indian jurisprudence which had treated the oath in abstract terms, my doctrine gave it teeth.

He urged me to publish an article and seek reviews from reputed jurists. I was honoured to be invited as a guest of honour at his book launch on May 30, 2015 at Raj Bhavan, Chennai, seated alongside the governor of Tamil Nadu and the chief justice of the Madras High Court.

In my speech, I briefly touched on the importance of the oath in safeguarding social justice.

Dhanapalan later facilitated a platform for me to present a paper in India titled “Constitutional Oath, Rule of Law, Judicial Review: An Alternative Approach to Basic Structure Jurisprudence”.

He was a rare jurist—open to competing ideas, even those that could challenge the very foundation of the basic structure doctrine in India.

His passing before the conference was a personal and professional loss. He had envisioned a future where my doctrine could reshape constitutional accountability.

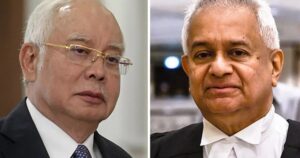

Another profound loss was Justice Gopal Sri Ram, who reviewed both my concepts — the oath jurisprudence and the University-cum-Court Annexed Arbitration model. He was a staunch proponent of the basic structure doctrine, yet he wrote:

“If embraced, this approach could restore judicial review to its rightful place—not as a ‘disabled creature with a thousand tongues and no teeth’, but as a principled and effective check on arbitrary power.”

Sri Ram was a Bencher of Lincoln’s Inn. A positive and powerful review by him on both concepts is a matter all barristers need to take cognisance of. His endorsement carries weight, not just within Malaysia, but across the Commonwealth legal fraternity.

Despite endorsements from two towering jurists, the legal fraternity in Malaysia has yet to embrace these doctrines. My Aluma Mark Chionso (2020) judgment, which elaborates on the judicial power vested in the oath, remains unchallenged in the Federal Court. Yet, my judicial journey was disrupted — not for lack of merit, but for daring to act in accordance with the oath and constitutional truth.

Dhanapalan planted the seed of exporting jurisprudence. Today, I have exported two doctrines:

- the oath of office jurisprudence

- the university-cum-court annexed arbitration, which is freely available at www.janablegal.com.

Both are designed to reduce case backlogs and enhance access to justice without legislative intervention, aligning with the Uncitral Model Law.

These doctrines also address the issue of constitutional seat-warming, as discussed in Manoj Narula (2014) by the Indian Supreme Court. I urge chief justices across Commonwealth nations to take cognisance of these concepts — not for personal recognition, but to uphold the judiciary’s sacred duty to deliver justice efficiently and affordably.

I remain hopeful that the current chief justice, who recently paid tribute to Justice Gopal Sri Ram, will honour his legacy by empowering these doctrines for the public good.

Read also:

The views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of FMT.