KUALA LUMPUR: On a makeshift stage before rows of empty chairs, a lively puppet show entertains both the living and the departed during the Hungry Ghost Festival.

The stage, known as Getai, is a live performance held during the Hungry Ghost Festival and Chinese temple deity birthdays, designed as entertainment for wandering spirits.

At Jalan Pudu, the Sin Kim Hong Puppet Show Troupe from Penang prepares for a Bu Dai Xi performance, or glove puppetry.

The show begins with a curated list of songs and Hokkien narration, drawing locals and migrant workers alike to listen to the melodies.

Co-founder, director, and performer Tan Lee Chin expertly manipulates the puppets behind the stage. Alongside fellow troupe members, she engages in playful banter with the puppets to the sound of traditional instruments, following a script that highlights the story’s narrative.

Glove puppetry originated in 17th-century Fujian, China, as a local opera performed with puppets. Performances often adapt folk legends, embedding moral lessons such as the triumph of the weak over evil and the importance of kindness.

“Every script we perform carries a message, like teaching younger generations that kindness brings good fortune and wrongdoing has consequences,” Tan said.

She views glove puppetry as central to the festival, a way to honour the gods who watch over devotees throughout the year.

“Glove puppetry can be performed anywhere, but it is always about paying respect to the deities. On important occasions, like deity festivals or birthdays, we perform to honour them,” she said.

Tan first encountered glove puppetry in her hometown of Taiping.

“I caught performances as a child and secretly learned by watching. I did not formally study under a master; I relied on memory and my own practice,” she said.

The Sin Kim Hong Puppet Troupe was established nearly seven decades ago by her husband’s grandfather, who brought glove puppetry from Fujian. Her husband, now the third-generation leader, continues the troupe.

Its oldest performer, 75, remains active, while the youngest is in his 40s. Yet the troupe faces an uncertain future, as few young people are willing to learn the art.

“Our work does not pay well. Most young people seek better income, so only family members continue,” she said.

Still, Sin Kim Hong performs across Malaysia, keeping their artistry alive for both the living and the deceased. For members dedicated full-time to the stage, the troupe is both livelihood and lifelong devotion.

“This is part of our cultural and spiritual life. As long as temples exist and people practise religion, glove puppetry will endure.”

Cultural exchange: Taiwanese opera singer joins Malaysian glove puppetry performance

The art even extends beyond Malaysia, attracting foreign artists to witness the cultural performance.

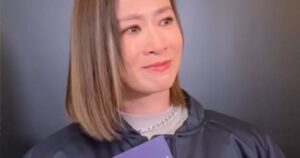

Taiwanese opera singer and actress Chen Yu Chiao, from a family of opera performers spanning three generations, joined Tan for this year’s Hungry Ghost Festival performance.

“In Taiwan, glove puppetry usually involves singers performing backstage while puppeteers handle the movements. Here, you sing and operate the puppet at the same time, which makes it simpler and easier for audiences to follow,” Chen said.

Having trained since age 12 and spent nearly four decades in Taiwanese opera troupes, Chen noted that Taiwanese puppetry often uses classical literary Chinese scripts. In Malaysia, the plays adapt familiar opera scripts, making the performance feel like opera without costumes or makeup.

Performing in Malaysia was also a moment of cultural exchange for Chen, a long-time acquaintance of Tan.

She shared Tan’s concern for the art form’s future.

“There is a shortage of trained performers. The older generation is ageing, and fewer young people are picking up the art. Without proper training, the stage may be filled by those performing for income rather than passion,” Chen said.

© New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd