She held them once, then they vanished.

A gold in the pentathlon. A silver in the 100m hurdles. Both from the 1971 SEAP Games in Kuala Lumpur.

For decades, the medals were missing — mishandled, misplaced, and ultimately forgotten.

Now, 54 years later, they will finally be returned to 84-year-old P Savithri.

It should be a moment of triumph. Instead, it feels like an indictment.

Hers was a career that blazed, then slipped into the shadows.

She trained without coaches, hauled her own gear, and relied only on grit.

Seremban’s Savithri was once among Southeast Asia’s finest athletes. At Stadium Merdeka in 1971, she took on the pentathlon and hurdles with a ferocity that set her apart from the rest.

Yet while her feats were cheered then, they slipped through the cracks of memory soon after.

“Sad to say, all former athletes are long forgotten or never heard of now,” she says. “In spite of all the previous newspaper reports about my missing medals, no action was taken.”

The apology that came too late

The medals were taken decades ago by a national athletics official for an exhibition, and never returned. Somewhere along the way, they vanished.

Now Malaysia Athletics has apologised. Secretary-general Nurhayati Karim admitted the mishandling, pledged reforms to safeguard athletes’ memorabilia, and promised a ceremony befitting Savithri’s legacy.

It is the right gesture. But it is undeniably late.

Fifty-four years is not just a delay. It is institutional neglect.

It is evidence of a culture where athletes are remembered only when anniversaries, media reports or national holidays force the issue.

Forgotten, until forced into the light

Former track queen M Rajamani has been blunt about it. Retired athletes, she says, are too often left to fend for themselves.

Yakeb, the national athletes welfare foundation, offers some financial and medical aid, but official appreciation is thin.

Savithri’s case is not unique. She is simply the one whose medals went missing, and whose story made it to print.

A nation owes its pride to those who built it, and it must remember them. A nation that forgets its pioneers erases its own history.

Yes, celebrate the moment. She deserves every cheer when the medals are draped around her.

She deserves to feel the weight of recognition that has been denied for so long.

But let us not stop there. Let this ceremony be more than a photo opportunity. Let it be the start of a reckoning with how Malaysia honours its sports heroes.

What if every former national athlete was properly documented, recognised, and remembered?

What if pensions, medical care, and community support were not acts of charity but commitments of gratitude?

What if national sports associations treated legacies not as tokens but as sacred trust?

The lesson of Merdeka

Malaysia is young. Sixty-eight years of independence is not a long time.

But it is long enough to ask: what does independence mean if those who built our sporting identity are left to the margins?

Independence is not just about flags and fireworks. It is about memory and gratitude.

It is about recognising the men and women who built Malaysia’s sporting identity when resources were scarce, when glory was earned with sweat more than sponsorship.

Savithri will finally see her medals again. That moment will matter — to her, to her family, to those who still care about sporting history.

But the bigger question is whether Malaysia will seize the lesson. Because medals can vanish. Memory should not.

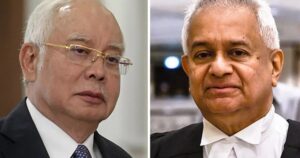

P Savithri. (Malaysia Athletics pic)

The views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of FMT.