They had not met in years. Time had turned one into Sarawak’s governor, the other into a man remembered for his unforgiving drill.

Now, head of state and drillmaster stood face to face again, a reunion charged with the weight of rank, memory, and respect.

Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar and Harbhajan Singh — protégé and mentor — reunited in Kuala Lumpur recently.

It was more than handshakes. It was recognition.

Wan Junaidi recalled the relentless drills that hardened cadets into officers. “Harbhajan made us into men,” he told his guests.

Harbhajan, 85, listened with quiet pride. After drilling a thousand trainees between 1962 and 1968, being remembered by a head of state was honour enough.

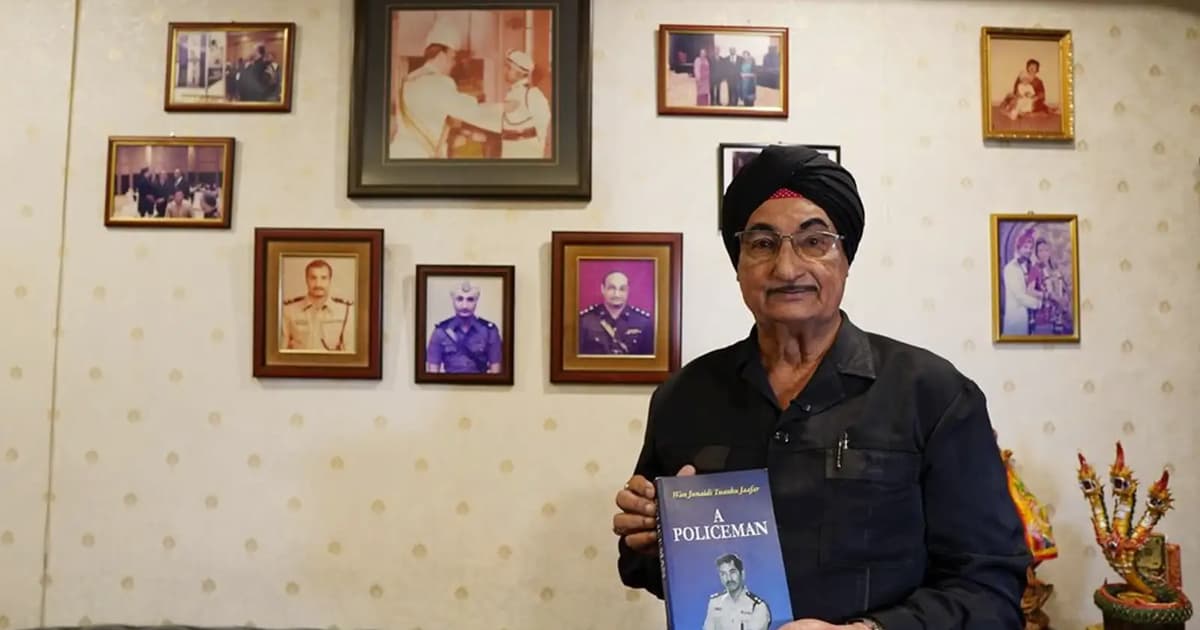

In his memoir, “A Policeman”, Wan Junaidi described his instructor as “ordinary and humble, fluent in English, very athletic, lean, mean-looking, tough and demanding.”

Behind the sternness was a code that shaped the young cadet’s life in uniform, politics, and now in the palace.

“Never bluff your way around,” Harbhajan had told his men. “Face life’s burdens head-on, no matter how painful.”

Those words followed Wan Junaidi through the jungles fighting communist insurgents, into Parliament as deputy speaker, Senate president and Cabinet minister, and today as Sarawak’s governor.

Time, truth, courage — etched into him by the taskmaster.

Harbhajan smiled. “For a man of such stature to remember me — I never expected it. That bond is the true reward.”

But Harbhajan was never just a drillmaster. He was something more.

He was Samurai.

The Samurai

The name came one night in 1971, at Sungai Gadut Estate near Seremban.

Four robbers stormed a gambling den armed with parangs and samurai swords. Most men would have ducked or waited for backup. Harbhajan did neither.

Lying in ambush, he spotted the den owner’s sword. In a flash, he snatched it and charged.

Steel met steel as he cut through the gang. Two robbers fell wounded, all four ended in custody.

Word raced through Negeri Sembilan: the fearless cop who fought sword-wielding criminals with their own weapon.

The underworld shuddered, colleagues saluted, and people whispered a new name with awe.

Samurai.

Even Tuanku Ja’afar Tuanku Abdul Rahman, the late Yang di-Pertuan Besar of Negeri Sembilan, called him “Shintaro”, after the swordsman in the Japanese TV series The Samurai.

From then on, Harbhajan carried more than a rank — he carried a legend, one that today lives on in Samurai Villa, his home in Taman Serene, Johor Bahru.

Fearless crime buster

The sword fight was only one chapter in a career written in fire.

As a constable in Seremban, Harbhajan once directed traffic when he saw a man sprint past clutching an envelope.

Suspecting something amiss, he chased and floored him with a flying kick. The man had just committed a robbery.

That single act of instinct and nerve earned Harbhajan a transfer to the secret societies branch.

From there, he built a reputation that terrified gangsters and impressed superiors.

His investigations sent 18 men to the gallows, and he shot dead seven in fierce encounters.

Harbhajan seized more than 28 firearms, including two Sterling machine guns, and one he had once lost in an ambush, only to snatch it back from a criminal’s hand.

He smashed the infamous “Whistling Gang” in Pontian, recovering 10 guns after a firefight.

Across Negeri Sembilan and Johor, he faced down armed criminals and solved many murder cases.

His daring whispered like folklore among colleagues. Gangsters knew the name. The streets respected it.

To fellow officers, Harbhajan was the man you wanted by your side when danger struck.

Samurai with a stick

If his sword was steel, his other weapon was wood.

On the hockey pitch, Harbhajan wielded the stick like a blade. Swift, precise, unyielding — his style mirrored the code that earned him his nickname.

From 1960 to 1974, he represented Police, Selangor, and Negeri Sembilan as a forward on the left flank.

Teammates said he could turn defence into attack in a heartbeat, cutting through opposition lines with stickwork as sharp as a katana’s edge.

As coach, his legend grew. In 1974, he led Negeri Sembilan to a Merdeka Cup triumph. Two years later, he delivered their first Razak Cup title.

He later coached Johor’s Razak Cup and Sukma squads, attended an advanced international course in Karachi, and in 1993 led Thailand’s women’s team at the SEA Games in Singapore.

As an administrator, he now leads the Johor Bahru District Hockey Association, which he proudly calls the finest district body in the country.

Everywhere he went, he preached discipline, precision, courage — the Samurai code in sport

Shaping men, shaping leaders

That same code shaped not only hockey players but leaders of state.

Wan Junaidi was one of many cadets under Harbhajan in Kuala Lumpur in 1964, when the “commissioner’s cadets” programme recruited Sarawakians into the police force

He went on to practise law, serve three prime ministers, hold three ministries, rise to deputy speaker, lead the Dewan Negara, and ultimately became Sarawak’s governor.

Yet in his memoir, Wan Junaidi paused to acknowledge a corporal: the man who taught him punctuality, truthfulness, esprit de corps, and courage.

For 16 months the book sat unfinished, as Wan Junaidi refused to publish until he tracked down Harbhajan — the missing piece of his story.

That, more than any medal, is the measure of a mentor.

Legacy of the Samurai

Harbhajan was born in 1941, the son of Amar Singh, a cook for Sikh policemen and Punjabi gatherings in Seremban, who doubled as a special constable and later a priest.

In 1952, Amar survived a communist ambush at the Shell oil depot in Bukit Tembok, fending off four attackers and injuring his hand. That act of grit left its mark.

Inspired, Harbhajan rose from King George V School, where he was crowned best sports all-rounder in 1959, to a career that made him both a feared crime buster and a respected sportsman.

The family he forged

That code runs through his family.

Today, Harbhajan lives more quietly, surrounded by those who reflect his spirit.

He has two sons, two daughters and nine grandchildren — “my life now,” he says with a softness that tempers the old steel.

His eldest son, Baljit, once a national junior in hockey and golf, now directs a specialist security firm and even played a cop in the Malay film Belang.

Baljit’s son, Priitpaal, 11, also acted in the same movie and is showing promise as a young golfer.

Harbhajan’s other son, Keshmahinder, represented Johor in hockey, while daughter Selvinder Kaur continues to make her mark on the golf course.

The lasting bow

For Harbhajan, life has come full circle.

The man once feared on the parade ground and hockey pitch now finds his greatest pride in the cadets he shaped and the family that surrounds him.

In moments like his reunion with Wan Junaidi, the past doesn’t fade; it sharpens, reminding all that the Samurai still stands, still remembered, still respected.

His story is not closed. It lives on in every salute, every handshake, every memory of a man who turned steel into strength for others.