It took 40 years, but the record finally fell.

In Tooting, London, Sarawak’s Kristian Tung ran 8:15.81 for 3000m, smashing S Muthiah’s 1985 mark of 8:27.00.

For decades, the record stood untouched, almost untouchable. Kristian, only 21 and fresh from injury, changed that in one sharp run.

This should be cause for celebration. It also forces a harder question: why are Malaysia’s record books frozen in the 80s and 90s?

A breakthrough worth applauding

Kristian’s return to form was swift. At the start of the year, he was still recovering from a shin fracture.

By June, he was running 3:52.43 for 1500m, the fastest by a Malaysian this season. Earlier this month he dropped his 5000m to 14:15.85.

Then came Tooting, where he delivered his first senior national record.

The 21-year-old now balances studies at Loughborough University with training on British tracks.

He is also a triple Sukma gold medallist, set for a 10,000m road race in September before turning to December’s SEA Games.

With endurance runners often peaking in their late 20s, Kristian has time.

What he lacks is sponsorship and sustained backing, the support that could lift him from promise to podium.

Muthiah: relief, respect, and reality

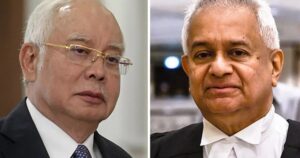

For Muthiah, who held the record for 40 years, the news brought no bitterness. His first response was simple: “It was time it happened.”

He added: “Records are not meant to gather dust. I’m glad Kristian finally broke it, because it shows Malaysians can still compete at this level. Waiting four decades is far too long.”

Muthiah knows the weight of expectation. In the 1980s, he was the country’s middle-distance king: three SEA Games golds in the 1500m, a national 1500m record of 3:45.99 in 1986, and that 3000m run in London.

But he also shaped others. In Cameron Highlands, he mentored a wiry teenager named P. Jayanthi.

Under his guidance she broke national records in the 1500m, 3000m and 10,000m in the early 1990s — all still standing.

“She had the talent, but needed the right environment. Cameron Highlands gave us that. It showed me what is possible when support and training meet ambition,” he said.

Yet, even he admits the system failed to sustain such breakthroughs.

“We can’t expect miracles from athletes juggling training with jobs or studies. If we want more Kristians, we need proper structures, not one-off efforts.”

Stuck in another era

Kristian’s run highlights the bigger problem: Malaysia’s athletics records are fossils.

Men’s 800m: B Rajkumar (1985), men’s 5000m: M Ramachandran (1994), steeplechase: N Shanmuganathan (1998). Race walks: a suite of marks from 1996–98.

On the women’s side: G Shanti’s 200m (1998), Josephine Mary’s 800m (1986), Jayanthi’s triple records (1993–94) and Yuan Yufang’s walks (1997–99).

Almost all were set in the 1990s. They remain intact. This is not a sign of greatness. It is a sign of stagnation.

Why the drought?

Malaysia has brought in foreign coaches from Cuba, Eastern Europe and beyond. Technical expertise is not the missing piece.

The problem is deeper: no continuity, no culture.

Talented youngsters peak at school or Sukma, then vanish. Pathways collapse. Sponsorship is scarce.

Even Cameron Highlands, once the natural base for distance champions, is underused.

As Muthiah put it bluntly: “Coaches can help. But without a system that supports athletes year after year, you are asking them to climb mountains in slippers.”

The global picture

Long-standing records are not unique to Malaysia. Japan’s women’s marathon best lasted 15 years. Paula Radcliffe’s world marathon record survived 16. The US women’s 400m hurdles record stood nearly two decades.

But in each case, systems kept producing contenders until one broke through.

Elsewhere, records tumble regularly. Norway has reset its middle-distance standards under Jakob Ingebrigtsen. Kenya and Ethiopia rewrite their books almost every year.

That is what a living athletics culture looks like. Malaysia’s looks frozen.

Beyond one runner

Kristian’s 15th-place finish in Tooting mattered less than the time on the clock. He proved Malaysians can still break barriers.

But unless more athletes follow, he risks being remembered as an exception, not a turning point.

The fixes are no mystery: proper funding, full-time athlete support, serious use of training bases, and a sponsorship culture that allows runners to train without distraction.

Without that, Kristian’s name will stand alone while the rest of the record book remains a museum of the 80s and 90s.

Muthiah is right — it was time. The bigger question is whether athletics in Malaysia will finally act, or whether we will be back here in 2065, still waiting for someone else to say the same words.

The views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of FMT.