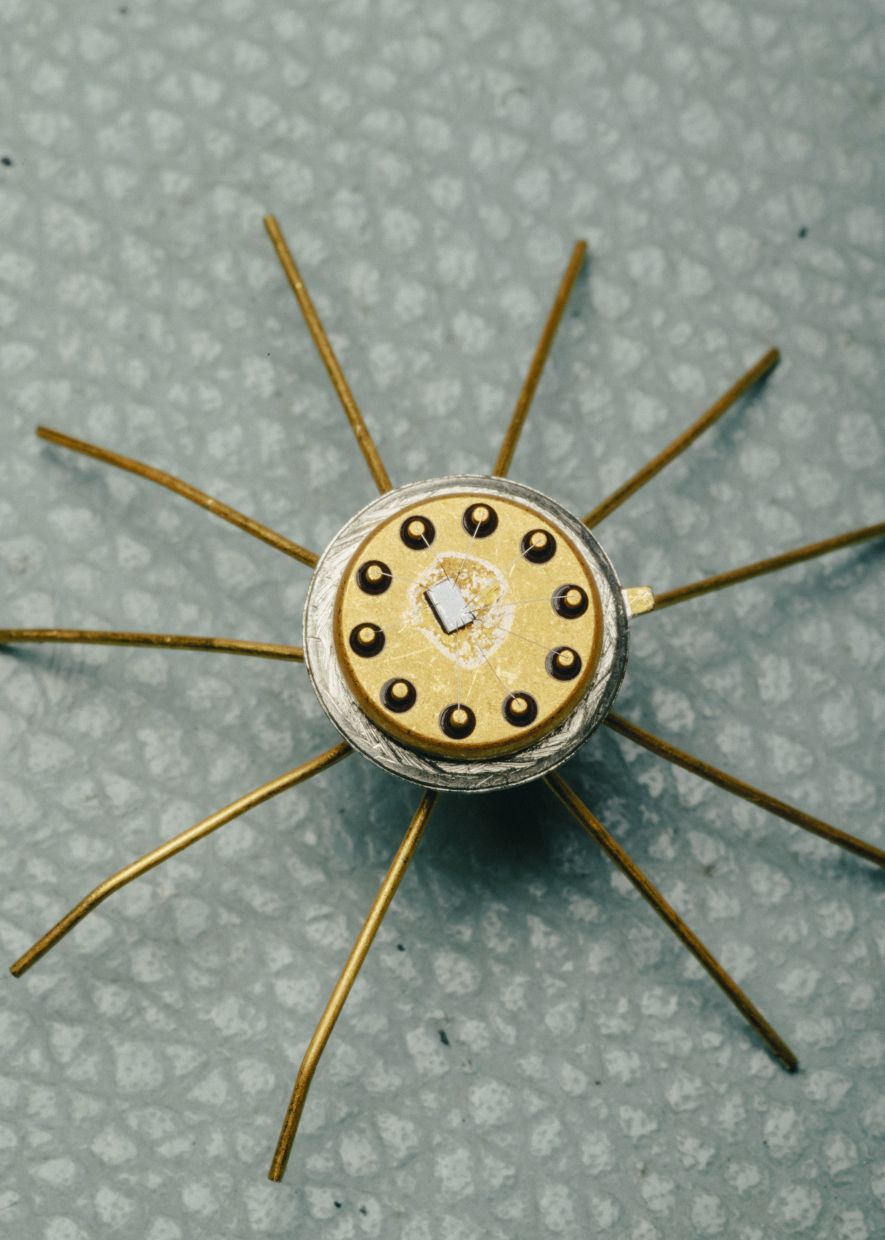

In 2020, Kenton Smith, an engineer, was peering through a microscope at electronic devices, admiring the intricate designs.

As he studied something called a voltage comparator, he saw a face staring back.

In one corner of the chip was a crude microscopic smiley face, about .004 inches wide, etched onto the surface.

Smith had made a hobby of examining silicon chips to study their layouts but had never come across such a personal touch.

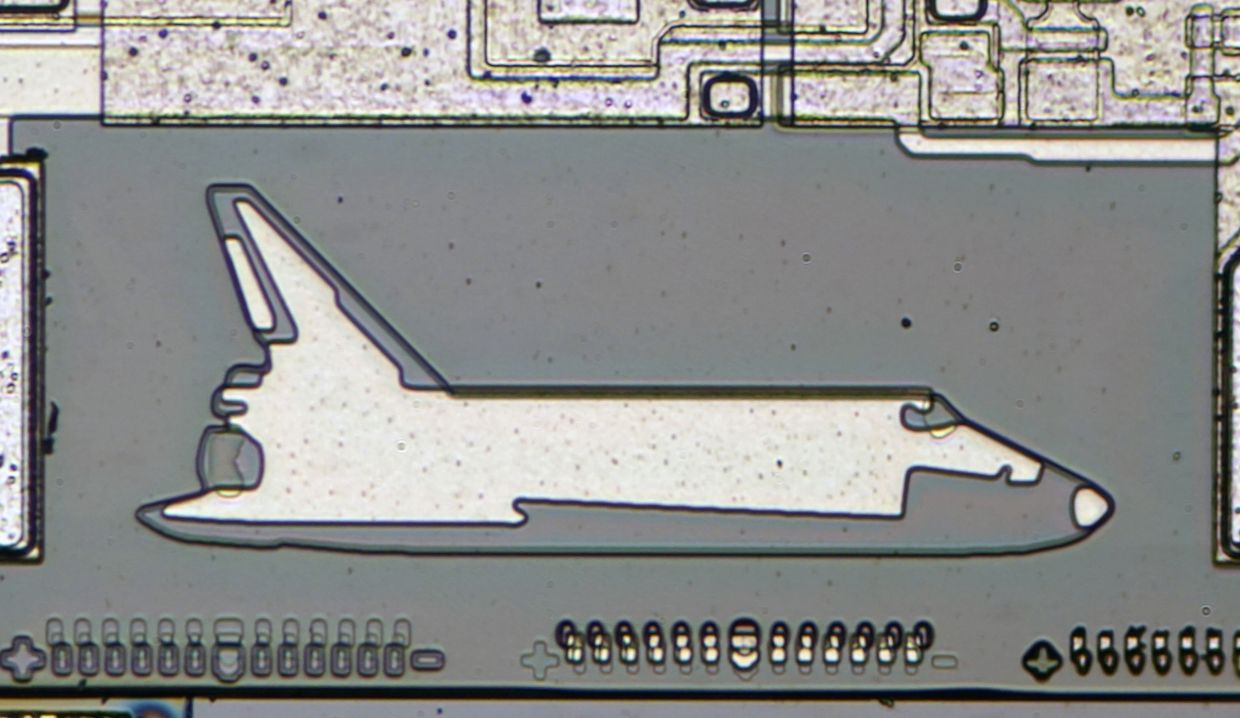

Smith had stumbled upon a relic of another era. The images, commonly known as silicon doodles, were used around the 1970s and after as a form of expression and to protect against technological theft. The doodles could be tame – the designer’s initials – or elaborate and whimsical, like a Tyrannosaurus rex driving a convertible.

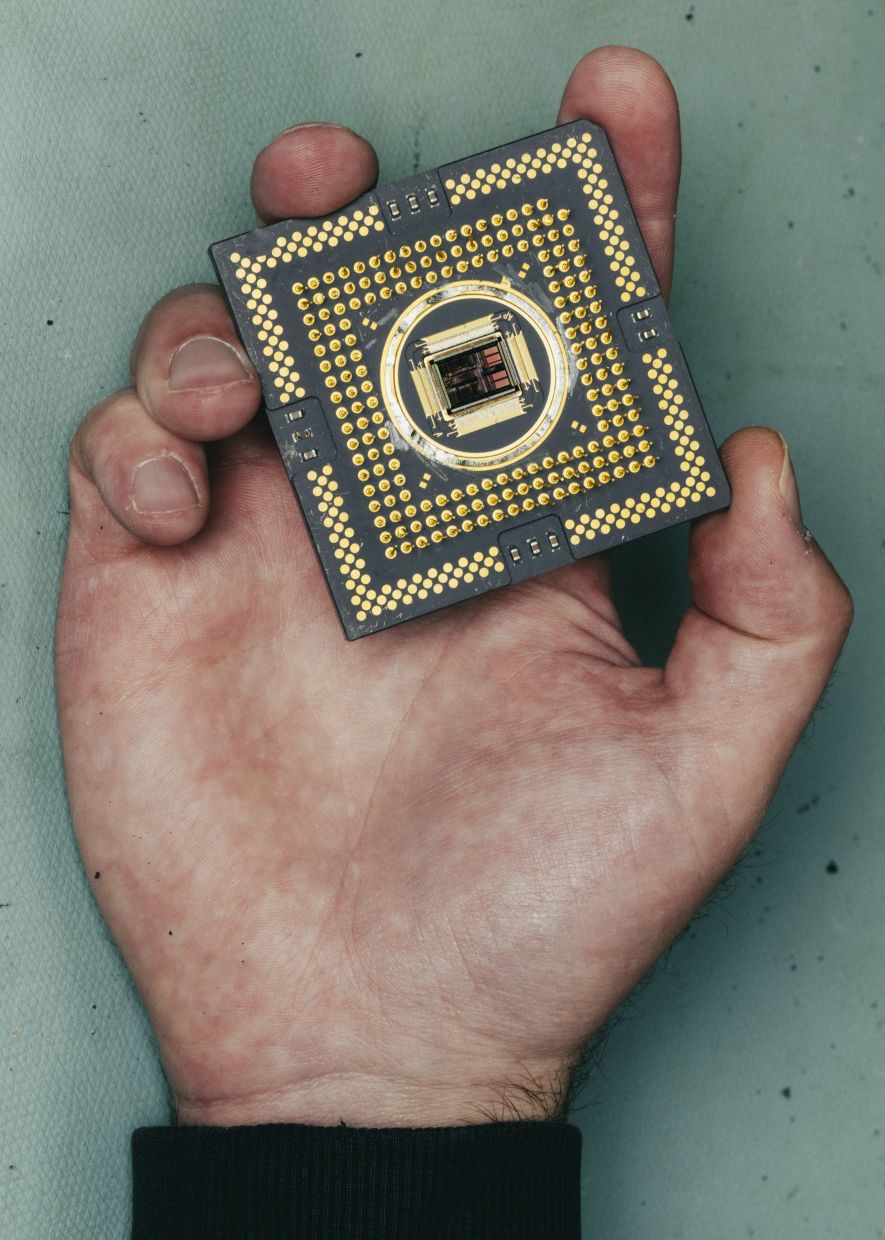

Although well documented, the doodles are a rarity, and the practice has largely been phased out. The hunt for them requires time, money for parts and an archaeologist’s spirit as collectors search flea markets and online auctions for the chance to unscrew hardware casings, whittle down chip caps and train their eyes to catch a glimpse of magic.

“It blew me away,” said Smith, 36, who is from Madison, Wisconsin. He now works in digital design, but from a young age, he was interested in electronics and computers. He was especially drawn to the “hidden beauty” of integrated circuits, he said.

He once spotted the tiny image of a pyramid on a chip and shrugged it off as a simple marker, but the smiley face opened a flood of questions. Through his research, he discovered a Florida State University website, the Silicon Zoo, which in the 1990s began cataloging the images made by chip designers.

“There’s so many different things that designers have left behind to leave their mark, and they don’t display it,” Smith said. “It’s just sort of hidden there, and no one’s ever going to see it.”

The main motivation for Smith, he said, is to archive the doodles before the interfaces they sit on are inevitably scrapped for the gold they contain. “It’s a race against time to find the chips while they still exist.”

When designers began to leave their marks on chips for devices like Intel processors and Nokia phones, they never intended for the world to find out. Teams at companies including AMD, Hewlett-Packard and Qualcomm would imprint the illustrations, many thinner than a human hair, onto unused interface real estate.

Many of the doodles alluded to a company’s heritage, like the Texas state flag on an AMD chip, or a mountain on one produced in Colorado. Others were inside jokes or calling cards. And designers appeared to have come up with the concept independently across companies and the country.

In the early 1990s, Deepu John had never heard of a silicon doodle, but he did have a very human desire to sign his work. He was earning a master’s in electrical engineering at the University of Michigan, and he added his initials to stamp his mark on a chip for an LCD display. When he joined Qualcomm in 1994 as an engineer, he was surprised to see that many on his team added personal emblems onto chips.

“They were the maverick days, like the early days of flying,” John said. “At that time, it could do no harm to the chip, so it was purely creative expression.”

John tried, with mixed results, to re-create a yacht from the period’s Old Spice advertisements. Another colleague who was thin drew elaborate muscles. The doodles were drawn with a chip design tool.

The most important reason behind the covert graffiti, John added, was for the doodles to say, “I’m signing my name on this chip, so it’s got to mean something.”

A small but passionate group of collectors tend to agree.

After Smith discovered the smiley face, he tried to track down more, buying scrap materials on eBay and posting the findings to social media, under the handle evilmonkeyzdesignz. Not every chip has a doodle – far from it. Smith said he spends thousands of dollars a year searching for the elusive Easter eggs.

Near Frankfurt, Germany, another doodle hunter searches the Internet and scours flea markets for parts that contain the images. Cedric, who posts under the handle CPU_Duke, has spent months searching for a particular doodle, but unearthing the silicon fossils is a reward in itself.

The thrill can lie in connections made over months between manufacturing locations and numerical codes on the casings and the chips themselves. After searching for a year for a Playboy bunny doodle he had seen on the Silicon Zoo, Cedric, who declined to share his last name, began to put the pieces together with number codes on integrated chips, or ICs.

“If you don’t find something, you just need to be lucky,” Cedric said. “I was just dismantling,” buying random hardware and looking, he added. But then he found a clue: An IC did not have a doodle, but it did have an identification number similar to one he was looking for. Soon after, he was able to cross-reference the digits and find the diamond in the rough.

He and Smith have put their heads together, too, for the more elusive doodles. Smith was searching far and wide for a “moose boy” chip – a cheery child with antlers – and had originally looked through a Nokia 5190 cellphone but had come up mooseless. Cedric later posted a similar doodle that was on a Motorola chip to Smith’s Discord channel. It was similar to the kind used in the Nokia, and the hunt was reignited.

Smith compared several boards for the Nokia model and noticed that the older versions had taller oscillator components. Inside one, he was finally able to dig up the hidden image.

“It’s a bit like archaeology,” Cedric said. “Hardware archaeology.”

The search can involve weeks or months of futile efforts, but the actual excavation of a silicon chip usually takes a matter of minutes.

If the lid over the chip is soldered on, a heat gun quickly melts the material, making the cover easy to flick off. Heat is also used on plastic epoxy packaging, but occasionally the plastic isn’t easy to separate from the silicon chip. In that case, Smith will put the casing in boiling pine gum rosin for 30 minutes to an hour to dissolve the remaining plastic.

Some hunters use stronger acids, which require better safety measures like ventilation. Using rosins and acids, though, runs the risk of discoloring doodles. When Smith uses a rosin, he does so in his garage with the door open while wearing a respirator mask.

A scalpel is usually used to get to the chip itself, which is then tweezed out and put under a microscope.

In 2025, it’s hard to imagine a doodle being made on an integrated circuit. The slightest deviation can be registered and potentially lead to a nearly imperceptible difference in a chip’s performance, leaving designers without the creative freedom they once enjoyed.

Still, as the technology they worked on evolved into smartphones and the current digital world, the doodles are simple reminders of the human behind the machine.

“I felt I got to work on a small piece of history at Qualcomm,” John said. And reminiscing about the art that he created, he added, “brings a smile to my face.” – ©2025 The New York Times Company

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.