Any move to open more dedicated autism education centres must come with a plan to ensure that there are enough qualified personnel, according to academics and experts.

For a start, Lau Choo Ying of Sunway University pointed out, building more schools without increasing the number of teachers is inadequate.

Meanwhile her colleague Audrey Ooi emphasised the need to qualify the term “trained” to differentiate the professionals with those who only shadow a senior staff, a concern shared by Malaysian Association of Behaviour Analysis (Maba) president Alexa Goh.

Lau, who is a programme leader for the Master of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA), said there is still a significant gap between the number of trained therapists and teachers, and that of schools. “This is a concern expressed regularly by families,” she told FMT.

She emphasised that a meaningful autism education programme must be more than just a building.

“If these centres aren’t properly staffed, they may look good on the outside but fall short in delivering real support. It can be disheartening for parents who expect more than just basic supervision,” she added.

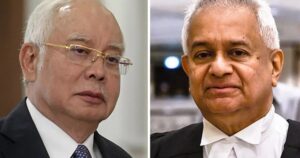

When tabling the 13th Malaysia Plan for debate in parliament on July 31, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim announced that dedicated centres for autistic children would be set up nationwide.

The move is said to be part of a broader strategy to expand support for persons with disabilities (PWDs), alongside plans to dedicate additional blocks for an integrated special education programme (PPKI) at 34 existing schools.

Lau said that to be effective, a centre must have an autism-friendly curriculum, individualised education plans (IEPs), and well-trained staff familiar with meltdowns, sensory regulation, and non-verbal communication.

She also pointed to the importance of frameworks like positive behaviour support (PBS), which help educators manage challenging behaviours with empathy and structure.

Ooi noted that the quality and accountability standards vary widely in in-house training.

“We have to ask what the word ‘trained’ actually means. Is it just shadowing a senior staff, or is it guided by certified professionals with ethics and standards?” she told FMT.

Citing international data to highlight the shortfall in qualified personnel, Ooi noted that only 57 Malaysians are certified by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB), with another 58 listed by the Qualified Applied Behavior Analysis Credentialing Board (QABA).

“That’s just over 100 active professionals, with some overlap. The numbers show we’re not there yet,” she said, adding that well-intentioned but poorly informed practices can hurt more than help.

Ooi also noted that most autism-related services remain concentrated in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor and without deliberate efforts to decentralise and retain certified professionals across the country, a truly nationwide expansion would be hard to achieve.

While she welcomed the plan, Goh also voiced concerns that well-meaning but undertrained staff could easily “misread” behaviour due to a poor understanding of autism.

“For instance, when a non-verbal child is in distress, it may be their only way to communicate sensory overload — but if the adult doesn’t understand that, they might respond inappropriately. That can be damaging,” she told FMT.

She said Malaysia needs to develop a sustainable, multidisciplinary workforce and shift away from “one-size-fits-all” models to more personalised and neurodiversity-affirming approaches.

Teresa Ling, a behavioural clinician and co-founder of The ABA Project, an initiative promoting evidence-based autism education in Malaysia, said poorly delivered interventions can reinforce challenging behaviours or set back development.

“Interventions should be grounded in data and delivered by properly trained professionals,” she said.

She called for stricter national standards on who can provide therapy and raised concerns about pseudoscientific treatments that continue to mislead families.