Katsuko Kuwamoto was just six years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She was at school only a few kilometres from the hypocentre and felt the shockwave rattle the ground beneath her.

Some memories are hers to carry, while others have been passed down by survivors recounting the unspeakable horrors.

“Some people were hit from behind. The air pressure was so strong that it made their eyeballs pop out of their sockets. Some of them were still alive, holding their eyeballs in their hands,” she said in her testimony to visitors at the Hiroshima Peace Hall.

Skin peeled off in sheets, as thousands staggered toward the rivers, desperate for relief. Many were completely naked, their clothes vaporised by the heat, while others dragged themselves along with pieces of their flesh hanging off their bodies.

“At 4,000 degrees Celsius, you can’t even imagine what happens to a human body.

“Because of the intense heat, people became extremely thirsty. Everybody ran to the rivers to quench their thirst.

“But their organs had been so damaged by the blast and the heat that after a sip of water, they died instantly.”

The seven rivers that once gave life to the city became silent witnesses to a grim procession of tangled corpses floating downstream.

In the days that followed, volunteers came from outside Hiroshima to retrieve bodies from the rivers, but the death toll was overwhelming.

Fuel shortages meant cremating the bodies took far longer than expected. The fires smouldered endlessly and the acrid smell of burning flesh hung heavy over the city.

“They burned the bodies for days. I thought that if I stayed in that smell, I would go crazy. I would lose my mind.

“I heard the smell somehow works its way into the brain, so maybe I did go a little insane because of it.”

The girl next door

Katsuko’s neighbour was a junior high student assigned to work at the post office that morning. As she approached the building, she greeted someone, stepping outside with a customary bow.

At that exact moment, the bomb fell. The blast knocked them both off their feet and flung their bodies through the air, rendering her unconscious.

“When my neighbour finally came to, she was surrounded by black flames and smoke. She tried looking for the person she had greeted, but instead found a corpse with its eyeballs gone.”

Half of the girl’s body bore the full force of the heat. With no functioning hospitals, her burns left thick keloid scars that never healed.

Years later, she developed spots she thought were acne but were subsequently diagnosed as skin cancer. Doctors had to cut them out, leaving large holes in her body.

Her thigh, nearly stripped away by the blast, healed with only a thin layer of skin. Despite this, she was determined to share her story.

“She couldn’t walk more than five minutes without collapsing because of her leg. But she wanted people to know.”

Until her passing, she continued giving testimonies — sometimes from a hospital bed, other times wheeled out to speak directly to students.

Katsuko drove her to events at schools and the Hiroshima Peace Hall, helping her tell their shared story. It was her encouragement that pushed Katsuko to start speaking out for herself.

‘Let Hiroshima and Nagasaki be the last’

Now, when Katsuko flips through the pages of her local daily, the images from Gaza and Ukraine feel all too familiar, harkening back to the chaos she survived as a child.

“War is a ridiculous thing. I see people fleeing with their babies, carrying their whole lives in their arms. I can only worry about how they’ll feed them. I want to see these wars end as soon as possible.”

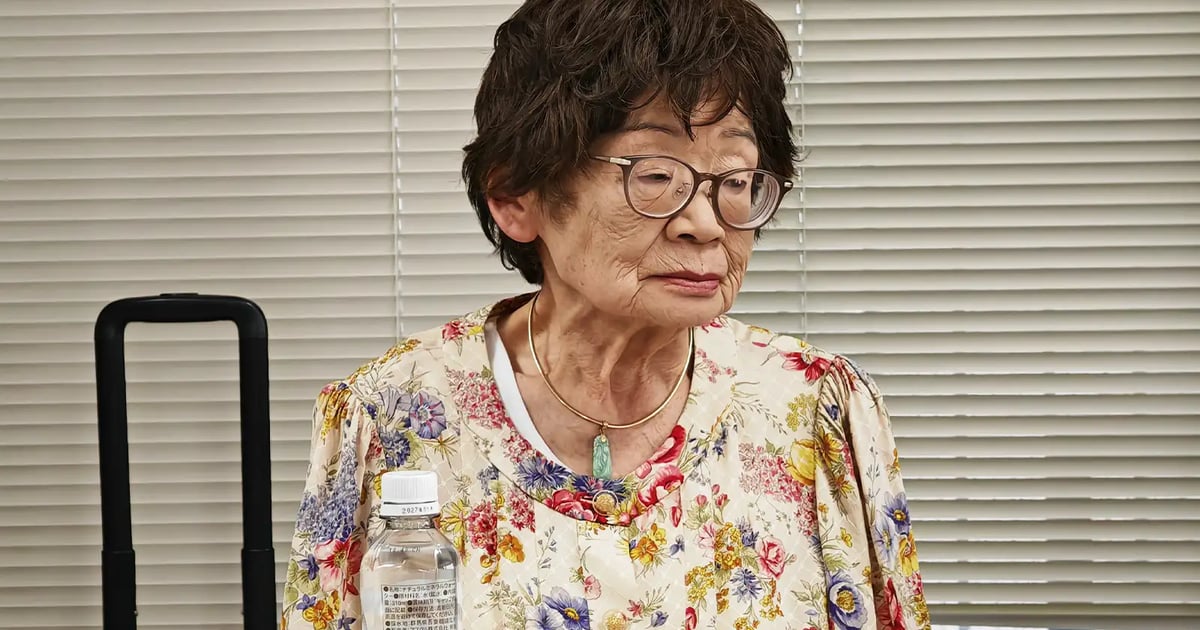

Now a great-grandmother, Katsuko, 86, has no patience for political brinkmanship risking nuclear destruction.

No one should thoughtlessly suggest dropping a nuclear bomb anywhere, she said.

Her plea is echoed in an elegy she wrote to her local newspaper, hoping the world listens, 80 years after humanity’s darkest day.

“To those who died on that day, I have something to ask when I meet you in heaven. How badly did your burns hurt? How badly did you want to moisten your swollen lips with cold water?

“To those who were swallowed by the sea after rushing into the rivers for water, how badly did you want your family to know how you were and where you were?

“To those who were holding their eyeballs with both hands, did you believe that you could bring back your eyesight if you cradled them?

“To the neighbour of mine who was erased, leaving his wife and four children behind, did you disappear before you had a moment to worry about your family?

“To those who fortunately survived the bombing, but had to fight cancers shortening your lives, how badly did you suffer fears everlasting?”