ON the glittering edge of Gelugor’s shoreline in Penang, where the tide washes against The Light Waterfront, a monumental form rises — curved and steady, like the shell of a turtle resting by the sea. Sunlight glints off its impressive façade and inside, the air permeates with the quiet hum of preparation.

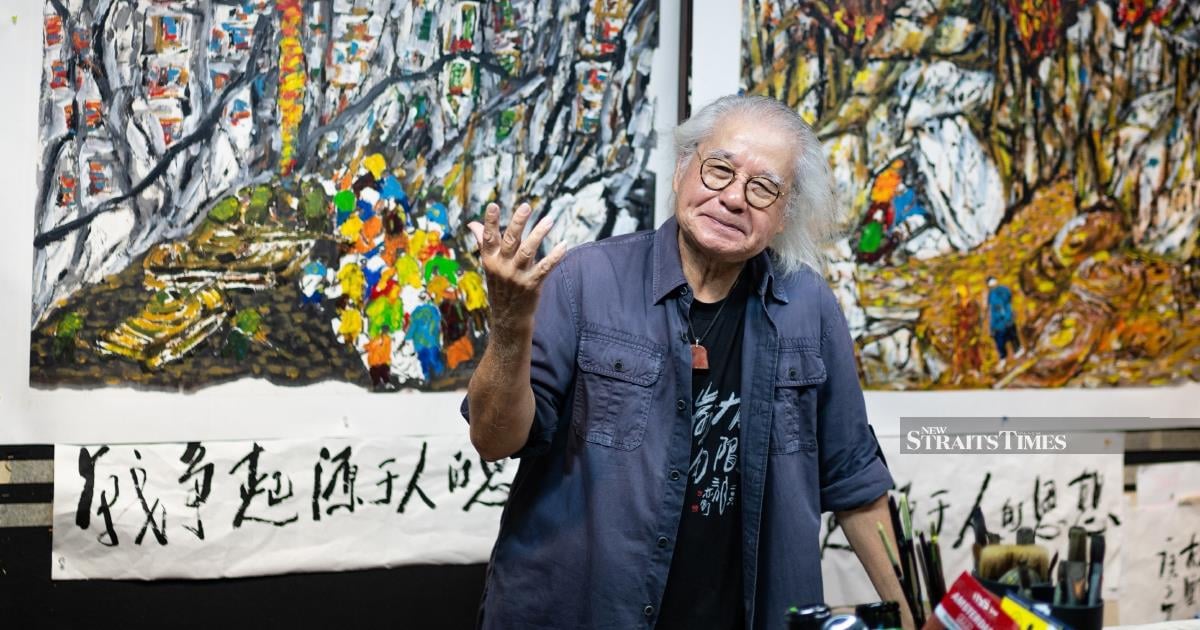

A gentleman, distinguished-looking with his owl-like glasses and shock of white hair, stands in the centre of it all, small against the sweep of his creation.

“Our human life, we’ve got a limit,” begins Professor Lin Xiang Xiong, voice low, as his gaze rests intently on the workers moving around like ants with a mission. Suddenly, his expression softens when he declares: “But human culture and art — there’s no limit.”

The Lin Xiang Xiong Art Gallery, located at the waterfront and opening next month, is more than a building. At eight storeys high and nearly 8,083 square metres of space, all together with a value of more than RM100 million, the gallery stands on the brink of becoming one of Malaysia’s most important symbols of cultural confidence and global connection.

[[nid:1311227]]

It’s also the physical manifestation of one man’s second life — a belief that art, at its purest, can heal the world that once broke him.

Embodying Lin’s lifelong philosophy of “Art for Peace”, the gallery will feature over 300 original artworks alongside a rotating collection of more than 1,000 pieces, tracing the artist’s six-decade creative journey across Asia and Europe.

DARKNESS TO LIGHT

[[nid:1311226]]

The affable Lin was born in 1945 in Jiuzhou, Guangdong, “…100 per cent made in China, export condition,” he jokes now, but his childhood was anything but light-hearted. His father left for Singapore when Lin was barely a year old. A decade later, his mother was killed in a political unrest.

“I don’t want to talk about my childhood,” he says, the words catching slightly. Eyes clouding momentarily, he eventually adds: “It is very, very difficult. My mother was only 36 at the time. I was 10. That was the darkness of my life.”

Even in those earliest years, Lin found a refuge in art. By the age of 7, he was painting and drawing the world around him with whatever materials he could find — a stick, soil, scraps of paper. It was a seed planted in hardship, yet destined to grow into a lifelong vocation.

Raised by his grandmother, he learnt early how to survive. In 1956, Lin followed his father to Singapore, a city of opportunity and struggle, carrying little more than determination and a budding talent.

The transition was neither easy nor forgiving. He worked by day in labouring jobs along the Singapore River and studied by night.

[[nid:1311225]]

“I had to work and study,” he recalls, adding: “At the time, it was a normal life — but I learnt discipline, patience and how to survive.”

He sold sketches to support his schooling and later earned a scholarship to study art in Paris.

“When I was in Paris,” recalls the youthful 80-year-old, “I worked in restaurants, washed dishes, made handbags. Half work, half study — that was my life.”

The years in Europe tested him, but they also crystallised a philosophy that would guide Lin’s life: art must be sacred, not commercial.

“I didn’t want to sell my painting,” he confides, adding: “To treat art as a way to earn money — that’s not the right way.”

[[nid:1311224]]

Returning to Asia in the 1970s, Lin had to navigate choices between teaching art, earning a living through design, or dedicating himself wholly to his vision. He chose a balance: working enough to survive while keeping his art — and his conscience — untouched. He worked as an interior designer to fund his art. Painting, he decided, must remain sacred.

Those years taught him the discipline that would define his art: long nights, unyielding patience and a refusal to give in. Even today, Lin sleeps barely five hours a night. “When I’m writing or painting, I don’t sleep,” he confides, adding: “Night time, I can concentrate better. Maybe it’s because I have lived with darkness; I feel comfortable there.”

Lin’s works — abstract yet anchored in human experience — speak of war, displacement, pollution and poverty. They pulse with empathy rather than despair. “When you suffer,” he tells me in his heavily accented English, “…no need to fear. If you get through, you will receive your brightness”.

ART FOR PEACE

[[nid:1311223]]

Lin shares that his vision extends beyond canvases. As president of the Global Chinese Arts and Culture Association, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Art and a visiting professor at Peking University, he has championed art as a tool for understanding, dialogue and peace.

[[nid:1311221]]

In 2016, he curated the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation’s (Unesco) exhibition Art for Peace — Cultural Dialogue between East and West, encouraging artists to act as peacemakers and protectors of humanity.

“Since wars begin in the minds of women and men,” he quotes the Unesco inscription, “it is in the minds of women and men that the defences of peace must be constructed”. He adds solemnly: “The mission of Unesco is not theirs alone. It is a responsibility for humanity as a whole.”

Lin’s philosophy is clear: even in a world of geopolitical and social conflict, art can serve as a universal language of empathy and reflection. Softly, he confides: “I cannot stop war. I have no power. But I have a golden heart. I want to share and serve all human beings — white, yellow, black — everyone!”

THE FINAL CANVAS

[[nid:1311219]]

From the outside, the soon-to-be-opened Penang gallery resembles a turtle — a creature revered in Chinese culture as a symbol of longevity and prosperity, and an emblem of Penang itself. For Lin, it’s also a metaphor for endurance: slow, ancient, steady.

“People ask, why a turtle?” he smiles, before adding: “Because our human life is short, but culture moves slowly, strongly, forever.”

Inside, the building unfurls like a journey through his own evolution.

One level traces six decades of painting — from 1965 to 2025 — while another houses his monumental works confronting war and environmental collapse.

There will be a floor for international symposiums, a library and spaces for visiting artists and students, nurturing understanding between East and West through the shared language of creativity. One level, overlooking the coastline, will even host cafes and small offices — because, he says, “culture must live with daily life”.

The space, shares Lin, is designed not as a mausoleum of art, but as a living organism.

[[nid:1311217]]

“Malaysia has always been a meeting point of cultures, a place where ideas, traditions and values flow together,” says the kindly professor.

Adding, he continues softly: “By anchoring this vision in Penang, I hope to honour that spirit and share with the world how art can transcend boundaries. This gallery is not only a tribute to Malaysia’s creativity, but also a reminder that peace and progress begin with understanding one another.”

[[nid:1311215]]

Lin speaks in a rhythm that is half-philosophy, half-poetry, his English threaded with cadence and pause. At times he slips into reflection, as if conversing more with the universe than with me.

“I finally emerged,” he says, quoting one of his essays, “from the ivory towers of scholars’ paintings to immerse myself in society, to observe human life in all its conditions. The true artist’s life is to break free from his own ego to embrace humanity as a whole”.

A pause ensues before Lin adds softly: “It is through serving humanity that I forged a new vision — that man lives only between Heaven and Earth.”

Then he smiles, quoting the ancient poet Qu Yuan: “The road is long, and the destination still far away; yet I cannot cease moving forward until I reach it.”

ART REMAINS

[[nid:1311211]]

The sprightly Lin’s life is both monumental and intimate. His family — a wife, a son and two grandsons — share his life in Singapore. “We’re happy,” he says simply.

The next generation of artists, he hopes, will inherit more than technique: they will inherit empathy, cultural awareness and a commitment to humanity. If there is something he is worried about, it is the thought that they could be in danger of losing their roots.

“Today, many young artists follow Europe, America… something modern,” he observes haltingly, adding: “But every race — Chinese, Malay, Indian — has its own life and perspective. They must expand their own culture and put it into art. They must care about human life.”

He warns that it’s not easy to be an artist. “You must set your goal,” he advises, adding: “It’s going to be a long journey and there will be a lot of difficulty. You have to work very hard, study hard, learn, learn, learn!”

Eyes gleaming under his glasses, Lin suddenly leans forward and declares: “Art and culture are the block in human life. Even if you disappear from this earth, your art remains.”

MONUMENT TO RESILIENCE

[[nid:1311209]]

By the time the Lin Xiang Xiong Art Gallery opens its doors next month, it will do more than house paintings. It will stand as a testament to a life that turned loss into purpose, suffering into creation, and hardship into a message of peace.

From the boy who drew shapes in the soil on his mother’s farm, to the young man washing dishes in Paris, and the elder statesman of art and peace — Lin’s story mirrors the long arc of survival itself. Every brushstroke, line of verse and wall of this new gallery carries the weight of that journey.

He often returns to a simple refrain: “When you suffer, no need to fear.” And perhaps that is what the turtle by the sea will mean for Penang — not merely a gallery, but also a quiet reminder that out of darkness, beauty can still rise.

[[nid:1311208]]

As he rises to prepare for a sneak peek into the new gallery, Lin declares with a small, almost mischievous, smile: “I’m 80 but I’m still strong. The road is long, yes, but I cannot stop moving forward.”

And as the tides wash against the shore at The Light Waterfront, one cannot help but believe him. Out of darkness, art has become a sanctuary — and where pain ends, peace begins.

© New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd