THE immigration agents’ tear gas grenades clinked and then exploded against the concrete, shrouding the block in plumes of white gas.

The dozen or so residents at the scene only screamed louder. “We don’t want you here,” yelled Rae Lindenberg.

The 32-year-old, who works in marketing, ran out of her apartment when she heard the shrill sound of whistles.

“Get out of our neighbourhood!”

The squad of agents had appeared in Lakeview last month, an upscale neighbourhood dotted with dog daycares, medical spas and vegan restaurants, hopping over a gate to chase down a construction worker who was handcuffed and shoved into a vehicle.

When Courtney Conway, a 42-year-old lifelong Chicago resident, heard about the chase through Facebook groups and text message chains, she hopped on her bike to join the protesters.

“We are not a violent city. This is not a war zone, and I think these guys are terrorising us and trying to incite us,” said Conway. “We want them out. We want them to stop kidnapping our neighbours.”

Chicago, a city of 2.7 million, has long been known as a patchwork of close-knit neighbourhoods.

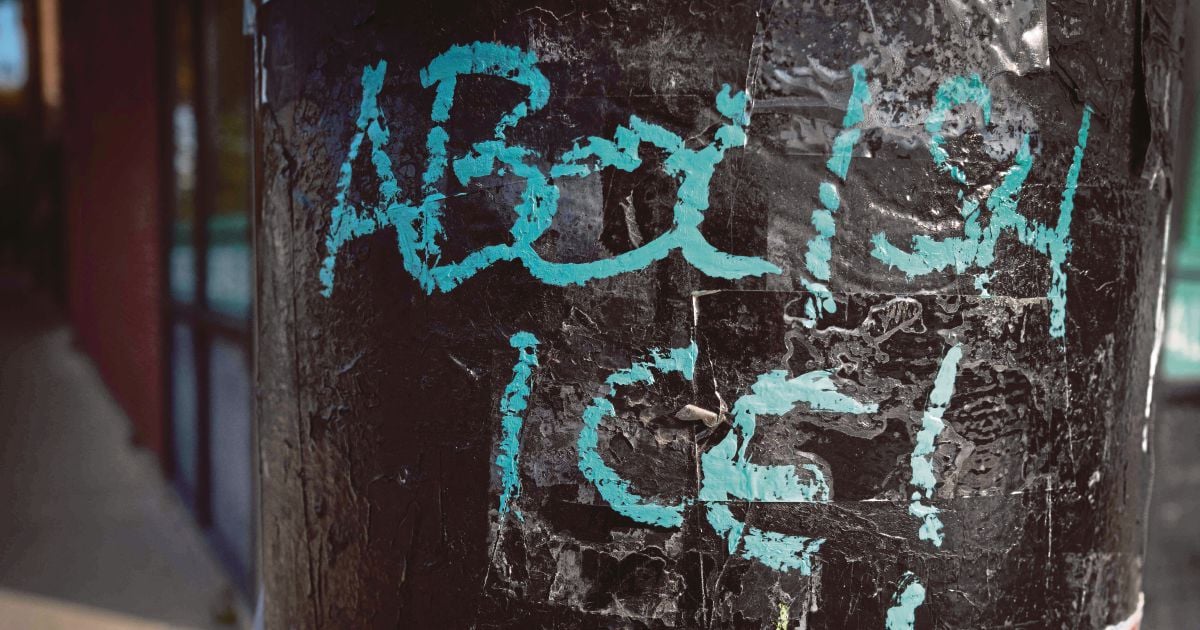

And since the city took centre stage of President Donald Trump‘s immigration crackdown in September, those neighbourhoods have mobilised against enforcement efforts, sometimes block-by-block.

That hyperlocal effort, spun off into dozens of chats on social platforms, has helped create a type of zone defence that, activists say, has slowed down immigration agents and in some cases forced them to withdraw without making an arrest.

When asked for comment, Tricia McLaughlin, assistant secretary for public affairs at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), said: “Our officers are highly trained and in the face of rioting, doxxing and physical attacks they have shown professionalism. They are not afraid of loud noises and whistles.”

In Facebook groups and on Signal chats, tens of thousands of residents regularly crowdsource information on immigration agents’ last-known locations, neighbourhoods being targeted that day and — importantly — the licence plates, makes and models of the rental cars used by agents, which can change daily.

Some United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)-spotting Facebook pages in Chicago have up to 50,000 members.

ICE and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents prowling city streets in unmarked cars are often trailed by drivers honking their horns and cyclists on an almost daily basis.

In some neighbourhoods, confrontations between CBP and ICE agents and protesters have grown increasingly heated.

Immigration agents have teargassed at least five neighbourhoods in the past month, according to a Reuters tally.

Last month, US District judge Sara Ellis directed agents to use body cameras and issue two warnings to protesters before using tear gas in a case brought by protesters, clergy and journalists.

Hours after the confrontation in the Lakeview neighbourhood, dozens of parents stood guard outside a school in Bucktown, another North Side neighbourhood favoured by families and young professionals, after hearing ICE and border patrol officers were in the area.

Some parents set up an informal checkpoint next to the school to check cars for immigration enforcement agents.

In Little Village, one of the city’s biggest Latino enclaves, businesses and residents locked their doors after activists warned them of approaching ICE and border patrol vehicles and at one point, surrounded vehicles to prevent them from making arrests.

Some protesters specialise in watching out for Black Hawk helicopters the ICE agents use to carry out surveillance of neighbourhoods, which don’t appear on flight-tracking apps and are often a harbinger of an impending raid.

On a recent Saturday morning, Brian Kolp, an attorney and former prosecutor, ran out of the house in his pyjamas when word spread throughout the Old Irving Park neighbourhood that immigration agents in balaclavas had grabbed a worker and a protester and shoved them into their car.

Other residents came out in Halloween costumes.

“People were yelling, and it was chaos,” said Kolp.

Soon after, he said, agents tossed tear gas grenades into the street and left.

The writer is from Reuters

© New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd