CONTENTIONS based on fundamentally erroneous premises may appear sound, even cogent, at first, but when examined more closely, do not have a leg to stand on.

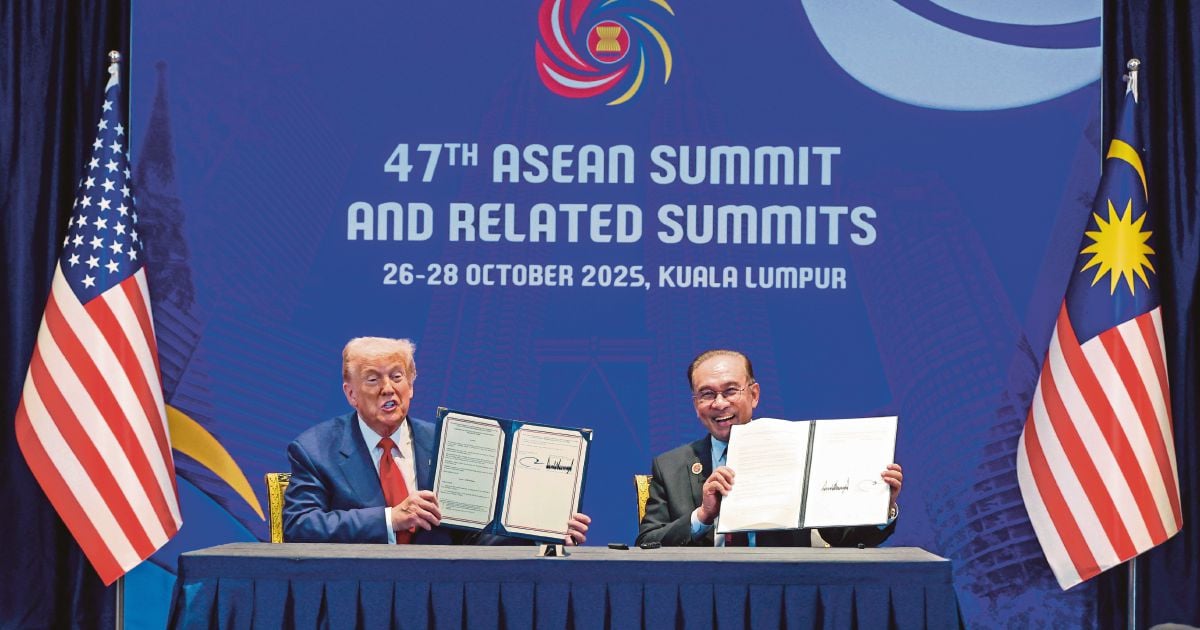

This goes for criticisms coming from detractors on the Agreement on Reciprocal Trade (ART) that Malaysia and the United States signed recently.

These critics conjure up the spectre of Malaysia being a proxy for America, held hostage by the demands of US mercantilism, and teetering on the edge of surrendering our economic and political sovereignty.

It would appear that we still have captive minds stuck in colonialist patronising mode.

Statutory and contractual interpretation of trade agreements is never an exact science, but to launch a full-frontal assault on a trade agreement based on myopic and narrow interpretations is an invitation to be hoisted by one’s own petard of logical fallacies.

Let us address the various contentions and assertions of these detractors.

First, Article 5.1(1) and the claim that we have signed a death warrant on our sovereignty. The entire clause would take up too much space.

So we will have to demystify the language and paraphrase it as follows: If the US imposes a Customs duty etc. on another country to protect its economic or national security interests, then Malaysia shall do likewise or agree to a timeline for implementation that is mutually acceptable, guided by principles of goodwill and a shared commitment to enhancing bilateral relations.

Detractors insist this is a mandatory provision which obliges Malaysia to adopt the same measure at the behest of the US. This is nonsense. In international trade, such language is used to establish a consultative alignment mechanism, conditional on mutual agreement. It is not a command clause.

Again, this is a fundamental misinterpretation because the phrase “through its domestic regulatory process” means that it is dispositive and that domestic law remains paramount. Where cooperation is conditioned on domestic legal process, it is not coercion.

Thirdly, the claim that the US gains veto power over Malaysia’s trade partners and deals, purportedly thanks to Article 3.3 on Digital Trade Agreements, which provides that Malaysia shall consult with the US before entering into a new digital trade agreement with another country that jeopardises essential US interests.

Yes, there is a mandatory duty to consult, but to be sure: consultation is conversation, not consent. This provision in no way obliges Malaysia to agree or follow the advice given during the consultation. Malaysia’s duty is discharged once we engage in the process of seeking views and opinions.

Treaty law draws a clear line between consultation and approval. The clause does not mandate compliance, let alone grant a veto. Malaysia retains sovereign treaty-making authority.

Fourthly, that Malaysia will be forced to target firms linked to China, Russia or others unpopular in Washington, purportedly on account of Article 5.1(2) which says Malaysia shall adopt and implement measures, in accordance with its domestic laws and regulations, to address unfair practices of companies controlled by third countries operating in Malaysia’s jurisdiction.

What’s the beef here? If anything, it is a good principle that underscores rules-based fair trading arrangements.

In any event, Malaysia already has in place such protocols which discipline economic actors under competition, customs and fair-trade laws.

Finally, there is the contention about the risk of alienating China and BRICS partners, and when that happens we lose our neutrality.

This is in for some serious non sequitur. For the sake of argument, how would alienating China and BRICS be tantamount to losing our neutrality? If anything, it means reinforcing neutrality. That will be the logical effect but this is purely an academic exercise.

This issue does not arise because our relations with China and BRICS are stronger than ever. So strong that we were being castigated for pivoting too much towards China and “selling out the nation’s sovereignty” as a trade-off for quick gains.

Our continued engagement with China is neither threatened nor diminished by constructive ties with the US. Nor do the US or Europe, Japan or India, expect us to abandon longstanding partners.

This is not the logic of the 21st century. It is the ghost of Cold War binaries that no longer hold sway in a multipolar world.

While there’s no doubting the importance of terms of endearment, the assumption that Malaysia cannot deepen relations with one major economy without losing the affection of another, borders on diplomacy as romantic melodrama: an imagined zero-sum contest in which nations behave like jealous suitors.

Our friends know that we value balance and openness, not alignment with any singular pole of power.

Let us be clear: Malaysia does not barter sovereignty for convenience. We have never done so, and we are not about to start now.

Further, what the sceptics mistake, willfully or naively, for submission is, in truth, the steady practice of modern statecraft. There is nothing to fear but fear itself. To suggest that Malaysia loses independence whenever it cooperates betrays a shocking lack of understanding of diplomacy and what it entails.

When global norms align with our interests, we act. We chose our own path in relation to Iraq. We maintain our own approach to the South China Sea. We continue robust economic ties with China, the US, the Gulf, Europe, and others.

Above all, we have remained steadfast in our principled stance on Palestine by doubling down on our condemnation of the genocide in Gaza.

Is this the behaviour of a nation waiting for permission?

Sovereignty is not demonstrated by reflexive rejection. Nor is it compromised by selective agreement. It lies in the freedom to choose and the maturity to exercise that freedom wisely.

To portray Malaysia as a reed bending willy-nilly to foreign winds is to turn a blind eye to decades of consistent foreign policy.

Nothing in the agreement obliges Malaysia to adopt punitive measures simply because another state does so. Claiming otherwise is to abandon the text entirely for speculation.

This government has articulated a sophisticated view of sovereignty, one the prime minister himself has emphasised: sovereignty today is not isolation. It is the ability to safeguard national interests through engagement while retaining the capacity to say no when necessary.

Malaysia’s tradition of non-alignment has never been a doctrine of avoidance. It has been a discipline of engagement without servility, pragmatism without fear, and partnership without loss of self.

That tradition continues. The ART does not upend it. It affirms it. We have always chosen our partnerships based on national interest, and we will continue to do so.

Those who suggest otherwise see shadows where there are none and threats where there is only the steady exercise of national agency.

Malaysia charts its own course, speaks in its own voice, and will not allow others to define our posture by their anxieties or assumptions.

In a region where great powers press their interests, Malaysia has never survived by hiding.

We have endured and prospered by standing, by engaging, and by deciding for ourselves. That is not surrender of sovereignty. It is the fullest expression of it.

The writer is chairman of the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia.

© New Straits Times Press (M) Bhd