SEMPORNA, on the edge of Sabah’s east coast, is where most tourists begin their journey to the stunning – and world renowned – dive havens of Sipadan and Mabul islands.

Overlooking the aquamarine expanse of the Celebes Sea, the town’s name means “perfect” in Malay but nowadays it’s sadly become known by another moniker: “Asia’s dirtiest town”, as dubbed by travel blogger Ben Frier in a video that has gone viral.

The video, replete with images of waterways choked full of trash and debris, sparked a war of words between Housing and Local Government Minister Nga Kor Ming and Semporna MP Datuk Seri Mohd Shafie Apdal.

Whatever the outcome of the argument was, however, it’s clear to see that the entire state of Sabah – and not only Semporna – has a real problem with waste: a half-day cleanup programme around Kota Kinabalu in August collected over 59 tonnes of trash and over 140,000 plastic bottles.

And it’s about to get worse.

After some dithering, the Sabah state elections have finally been called; nomination day is on Nov 15 while polling will be on Nov 29.

In between now and then, on top of the usual political horse-trading, jostling, and tantrums, we can expect the usual barrage of billboards, banners, pamphlets, and posters to go up at every junction and on every wall in the inevitable flag war.

This does not include the waste and carbon emissions from the frenzied logistics of politicians, party workers, and voters that are anticipated to crisscross the state as polling day nears.

Trash talks

Often described as the largest peacetime activity undertaken by a country, general elections are massive, complex, and frankly, a logistical nightmare costing millions of ringgit to run and leaving tonnes of waste in their wake.

According to a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report, “Elections for People and Planet: A Practical Guide to Managing Environmental Impacts and Risks of Electoral Processes”, large-scale electoral operations inevitably leave a significant environmental footprint.

“Fortunately, advances in technology and a wealth of global experience present ample opportunities to reduce the environmental impact of elections without compromising their quality or integrity,” it said.

During Malaysia’s 14th General Election in 2018, polling day was on May 9, and general waste collection in May that year rose to 269,042 tonnes from 250,266 tonnes in April, according to landfill operator Solid Waste Management and Public Cleansing Corporation in its 2018 annual report.

Under Section 24B of the Election Offences Act, candidates have 14 days after polling to clear up their campaign flags, banners, and posters. If they fail to do so, their campaign deposits – RM5,000 for Parliament seats and RM3,000 for state seats – are forfeited.

The state elections officer will then remove the remaining materials, charging the costs against the deposit. Should the cleanup costs exceed the deposit, the difference becomes a debt the candidate owes the Federal Government and it may be recovered from the candidate accordingly. Enforcement of this provision is carried out by a team that includes representatives from the Election Commission (EC) and local councils.

However, the Act – which was passed in 1954 at a time when debate on climate change wasn’t even on the horizon – makes no mention of how the waste should be disposed of or that recycling must be considered.

While the Sabah polls may not be a general election, a concern is that the state, as pointed out, already has a problem with waste management, and the polls are going to add to it. In the past, much of the clean-up of leftover party paraphernalia in Sabah was usually left to local councils and private waste companies.

Promises, posters and plastic

Greening Malaysia’s elections, says Malaysian Nature Society (MNS) president Anna Wong, begins with rethinking how we engage the public.

Traditional campaign materials such as banners, flags, and pamphlets, she points out, generate a significant amount of single-use waste that often ends up in landfills or drains.

“A greener alternative is to transition towards digital campaigning, supported by community-based engagements such as townhall sessions, small dialogues, and media interviews, which have lower carbon footprints and longer-term impact.

“The EC could also introduce guidelines to limit the amount and size of printed materials produced, encourage the use of ecofriendly inks and recycled paper, as well as require candidates to submit waste management plans as part of their campaign permit application.

“Incentivising the use of biodegradable or recyclable materials for banners and streamers would help,” says Wong, who was previously Sabah MNS chairman.

“Additionally, shared platforms for candidate information, official websites, or QR-coded manifestos could replace the need for mass printing while promoting transparency and accessibility.”

While digital campaigning may sound far-fetched, especially when there are still blind spots for Internet reception in Sabah, vote canvassing went virtual during the 2020 state elections when the Covid-19 pandemic struck, so there is precedent showing that it is viable.

Even if we can’t make elections greener right now by reducing carbon emissions with digital campaigning or cutting down on paper and plastics, there are still measures that can be taken immediately in waste management. For instance, while political parties are currently held responsible for post-election clean-ups, making the proper segregation of campaign waste mandatory would help deal with the waste better.

“Moreover, collaboration with local waste collectors and recycling organisations before the campaign season begins can ensure smoother coordination once the election ends,” Wong adds.

According to a local party worker, in Sabah, it is understood that contractors hired to put up party paraphernalia during campaigning are also often responsible for removing and dismantling them in the aftermath as “part of the deal”.

However, again, there’s no by-law or rule requiring contractors to recycle these materials or even to properly dispose of them.

Some of the materials left over from the last state election have been salvaged and reused by groups of undocumented and stateless people in cities like Kota Kinabalu. Campaign materials such as billboards are often spotted in their squatter settlements.

Digital first?

What with all the calls by election watchdogs for the EC to implement online voting (ie e-voting), will this work as well to reduce the carbon footprint?

Wong feels that while e-voting can theoretically reduce paper use and carbon emissions associated with election logistics, its implementation in Malaysia still raises concerns about cybersecurity, data integrity, and voter trust.

“E-voting systems must guarantee confidentiality, authenticity, and resilience against manipulation or hacking, standards that are difficult to meet without strong institutional safeguards and digital literacy among all voters.

“Before we leap to full e-voting, hybrid measures such as digital voter registration, transparent e-monitoring of results, or partial electronic systems within secure environments could be a practical first step,” she says.

Wong says just as candidates are expected to adhere to financial and ethical guidelines, environmental responsibility should be made a part of democratic accountability.

“Candidates should be required to comply with green rules, like responsible disposal of campaign materials, caps on printed media, and reporting on their campaign’s environmental impact.

“This would not only reduce waste but also set an example of sustainable leadership,” she explains.

Embedding environmental stewardship in the country’s democratic processes would remind both politicians and voters that caring for the planet is also a civic duty, adds Wong.

Counting the carbon cost

But elections aren’t just leaving an environmental impact; they are being impacted by the environment as well.

According to the same UNDP report mentioned above, extreme weather exacerbated by climate change is affecting elections in many countries.

International Foundation for Electoral Systems president and CEO Anthony Banbury writes that over the course of four decades, extreme weather events and natural disasters have become increasingly present in election operations, planning, and risk management.

Banbury offers an example: In Fiji in 2018, voting had to be postponed at 25 polling stations due to rains and flooding. As a result, a reserve site now has to be identified for every polling station by the country’s election authority ahead of any polls.

Fiji, as an island state, is extremely vulnerable to the impact of climate change such as sea level rise, changes in rain patterns, and coral bleaching from warming oceans.

The UNDP report urges authorities like the EC to plan for, among others, extreme weather, displacement, and infrastructure damage; to set up reserve polling sites, adjust polling hours for heat, and ensure safe transport and shelter; and train their staff for emergency response.

Voter access, the report stresses, must be maintained under crisis conditions.

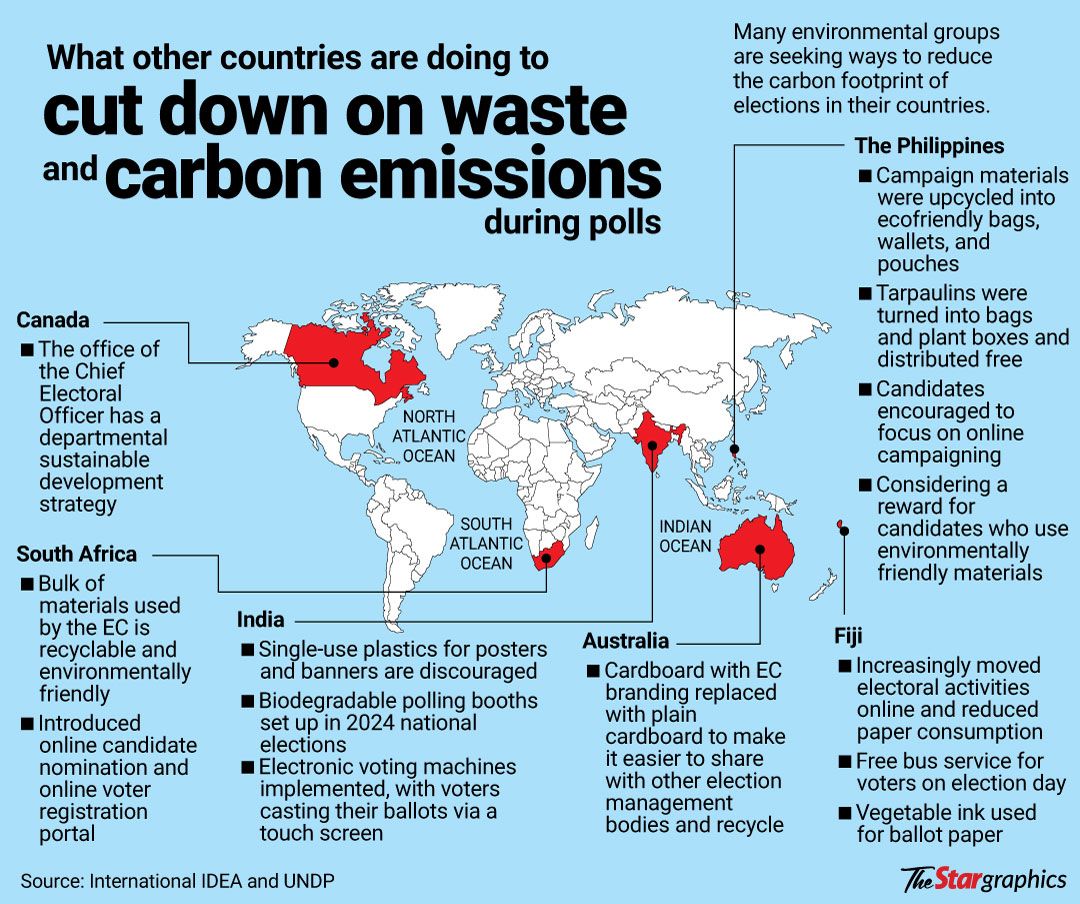

Many countries are already implementing changes. The Intergovernmental group at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance points to examples of innovations in Australia, India, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka that have managed to cut down on waste and emissions during elections (see graphic).

For instance, the EC in India urges political parties and candidates to avoid the use of plastic or polythene for posters and banners and, in 2024, introduced biodegradable polling booths.

A political party in Sri Lanka, the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna, even tracked carbon emissions from vehicles and electricity used during its campaign in 2019, and planted trees to offset the environmental impact.

Even in Malaysia, in the last General Election in 2022, many political parties streamed their ceramah and events live over social media platforms like TikTok.

Green politics usually refers to backing candidates who champion environmental protection. That still remains vital, as demonstrated by the election of US President Donald Trump, who has reversed subsidies for electric vehicles and approved new oil and gas drilling in Alaska, destroying the climate change mitigation efforts of the world’s biggest polluter. But green politics today must extend beyond candidates and platforms. The democratic process itself must also go green for the sake of the planet, and for the integrity of our vote.