Having lived in safe Hong Kong all her life, Nancy never imagined that an overseas job would lead to forced labour in a scam farm, a harrowing experience that lasted for half a year before she could be reunited with her family.

“I was living a life worse than death, surviving purely by willpower,” said Nancy, who is in her twenties.

Like thousands of others lured to Southeast Asian scam farms, Nancy was hoping to make some quick money when a “friend” referred her for a job making cross-border purchases in Thailand, she said.

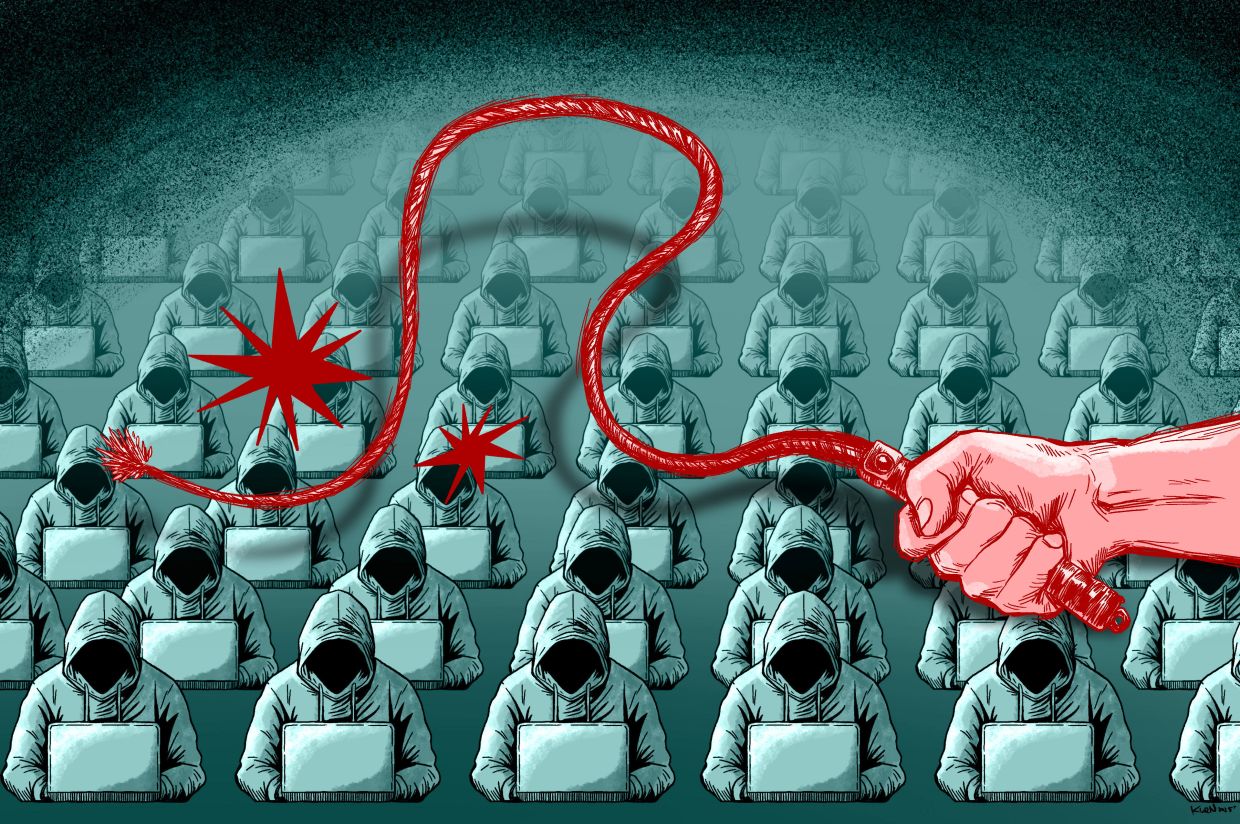

Instead, she only passed through Thailand and was taken to a scam farm in neighbouring Myanmar, where she was forced to try to swindle people, primarily targeting wealthy elderly Americans through everything from get-rich-quick schemes to fake online romances.

Also trapped in a Myanmese scam farm nightmare for a few months was fellow Hongkonger Eric, 30, who fell for an advert promising quick cash in Thailand.

The pair, who considered themselves among the “lucky” ones who later managed to flee, shared details of their plight and the operations of the scam farms to raise awareness about the dangers and help save others still trapped.

“I hope to share all my experiences to emphasise the importance of staying alert and being cautious. It is crucial not to chase quick money and to raise awareness about these issues,” Nancy said.

Eric and Nancy said that to align with US time zones, their work day stretched from 10pm to 7am and could last 18 hours if they did not meet their scam targets.

Each scammer was given four mobile phones and a computer to connect with “potential clients” by using various apps, including Tinder and TikTok, to find targets, Eric said.

Their daily key performance indicator (KPI) was to obtain two new phone numbers from their social media app contacts, which would be further developed as their potential targets.

Junior recruits such as Nancy were tasked with making initial contact and building up connections, with leads passed over to senior workers for the actual scamming.

Clear ‘career path’

Success would come with substantial rewards – for instance, scamming US$10,000 from a victim would earn them 10,000 yuan, according to the pair.

There was a clear “career path” for good performers, with promotion to group leader managing about six juniors and responsibility for their team’s scam quotas, the pair said.

Group leaders earned a fixed salary of more than 10,000 yuan per month with commissions on top, but they needed to ensure their team met its targets. Above the group leaders was a supervisor overseeing their operations.

However, as a scammer, Nancy was in a constant battle between her conscience and her need for survival.

“One of my targets, a photographer, told me that he had been scammed twice … and I still needed to pretend to be sincere and nice and scam him again,” she said.

“I had no choice but to survive.”

She said she only had “success” in one case. As she was green, Nancy said she was not involved in the subsequent scam and she was not even sure how much she had “earned”.

Nancy said she witnessed how a man with a prosthetic limb was still forced to work. The man had one of his legs broken after being beaten up by the syndicate as a punishment and lost the limb.

“As long as you have hands, you have to work,” Nancy recalled her boss telling her.

She said she had also learned that some people who could not bear the sense of hopelessness and harsh punishment killed themselves there.

Apart from being beaten up, other common types of punishment included whipping, electric shocks or being locked in a room with a black bear for a night, they said. Some punishments were carried out in front of others held on the farm.

Nancy said she was once hung up by her hands after she failed to meet the targets.

“My hands were tied, and I was suspended in a dark room with my feet barely touching the floor,” she said. “I cried every day, day and night, as I once could not see any hope of leaving.”

According to the book No Way Out: Modern Slavery Behind the Scam Curtain published in July by former district councillor Andy Yu Tak-po, who has been helping the families of Hongkongers trapped in Southeast Asia since 2022, there were far more unimaginable scenarios, including gang rape.

Victims told Yu that a serious flood at their scam farm turned out to be one of their “happiest moments”, as they were spared from working because of the limited electricity supply and slow network.

Apart from work, Eric and Nancy said they were given 30 minutes to two hours of free time every day before their scheduled sleeping hours.

They said they stayed in hostel-like dormitories, with eight people sharing a room of between 800 and 1,000 sq ft.

Eric said he arranged to live with people from Hong Kong, mainland China, Taiwan and Malaysia.

Life is good for some

Apart from dormitories, Eric said the scam farm had luxury villas and entertainment facilities such as a casino and even a brothel where local prostitutes worked.

While the scam farm had a convenience store for purchasing daily necessities, prices were extremely high. Eric said a lip balm stick cost a few hundred Hong Kong dollars.

Both he and Nancy said no one was allowed to use their private mobile phones to prevent them from contacting their families or seeking help.

Anyone caught trying to escape faced harsh punishments, including skin burns, according to the pair.

“A man had his skin burnt until he lost consciousness. He was then woken up by having water pouring on him,” Eric said, recounting a scene he was forced to witness as a deterrent.

But successful scammers enjoyed a wider range of entertainment options including karaoke, being able to buy their own television sets and visiting the brothel or casino during their free time – if they could afford such expenses.

“Some even enjoyed life so much that they did not want to leave,” Eric said.

But for Eric and Nancy there was no enjoyment, and all they wanted to do was to leave.

Researchers have said that the number of victims working inside scam farms is difficult to calculate because of the size of the compounds, the number of criminal networks involved and the ever-expanding operations across the region.

The grim reality of the scam farms, operated in lawless areas of countries such as Myanmar and Cambodia, often returns to the spotlight following high-profile cases, including the rescue of mainland Chinese actor Wang Xing earlier this year.

But many others who were not rescued had to find their own way out, and the process could be as challenging as surviving on the farm.

“I thought I was going to die there [while I was escaping],” said Eric, who managed to flee.

He said he first tried to befriend his supervisor to ensure lax supervision so he could secretly use his work mobile phone to seek help and contact his family, who later tried to reach out to relevant parties to secure his release.

Eric was allowed to leave the scam farm after his family paid a ransom of more than HK$200,000 following numerous discussions and with the help of a middleman.

However, Eric said the moment he left the scam farm, a tough and uncertain journey began, as he needed to make his own way to Thailand.

During a two-day trek, he crossed rivers on foot during torrential downpours, rode bulldozers and dealt with a driver arranged by an agent who disappeared for a few hours mid-journey, leaving him in the depths of despair.

“I had no idea where the driver had gone and just had to wait, as that was the only solution,” he said, adding that he was worried about being abandoned in the middle of nowhere.

“I was forced to walk through the night with no light and no sense of direction, relying solely on blind instinct to keep moving,” he said. “I could only relax once I arrived in Bangkok, Thailand.”

Eric considered himself lucky, as he understood that there were still around 8,000 people in the scam farm he stayed at when he left. How Nancy escaped cannot be revealed to protect her identity.

Free but traumatised

According to Yu, the ex-district councillor who has received requests for help to save victims since 2020, the most challenging part is negotiating with different family members who often differed in views on whether to report the case to police and tell the media.

He added that his main role was to coordinate with the victims’ families and, with the government’s help, to rescue those victims.

He also called on the government to review and toughen the relevant laws including the ones on trafficking in persons so as to impose a greater deterrent effect on scammers.

In a reply to the Post, the Security Bureau said that it had established a dedicated task force in August 2022 to coordinate follow-up work on cases involving Hong Kong residents allegedly detained in Southeast Asian countries.

It said the task force had received 29 requests for assistance, and 26 of those individuals had since returned to Hong Kong between 2024 and the end of July this year.

Two did not request help, and the task force was continuing to follow up on the final case, believed to be in Myanmar, it said.

Hong Kong police had also arrested 12 people in connection with this type of job scam case from 2023 to this June.

Another two people who were arrested in 2022 were charged with conspiracy to defraud and convicted, and sentenced to 36 months and 56 months’ imprisonment respectively.

In Hong Kong, conspiracy to defraud carries a maximum penalty of 14 years’ imprisonment.

For those who have been freed from the scam farms, the trauma is not over.

Nancy said her ordeal returned in her nightmares occasionally, and she could not share her stories with everyone.

“I would not tell [potential] employers I was working in the scam farm last year. I would lie and say I was on a working holiday,” she said, explaining that she hoped to avoid strange looks during job interviews.

“I am on my way to recovering from the trauma, but this experience has also allowed me to see how much my family loves me.” — SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST